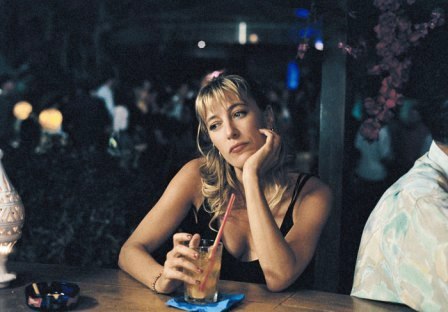

Opening in limited release last Friday, Francois Ozon's 5x2 (2004) confirms the director's place at the forefront of France's latest generation of filmmakers. Structured in five separate segments ordered in reverse chronology, 5x2 begins with a couple's divorce proceedings and then moves backwards, concluding before the "2" were together. As gimmicky as this might sound, Ozon's structure assures that its viewers will react differently to the film's two protagonists than they might have were the same events arranged chronologically. In other words, suspense becomes a matter of psychological revelation rather than the traditional mechanisms of cause and effect. Nevertheless, Ozon eschews lucidity. When an opportunity to clarify previously narrated actions does arise -- either in terms of what actually happened or in why a character may have behaved in such and such a way -- Ozon refuses to comply.

Batman Begins plays by very different rules. In Christopher Nolan's origins narrative, the future contours of the Batman persona are psychologized to painstaking -- and painful -- extents. Jung is the explicit point of reference here, in everything from Bruce Wayne's motivations to the villainous archetypes that populate Gotham.

Yet, if Batman Begins suffers from an overdetermined application of psychoanalytic theory, this is about the only level where it proves lacking. Otherwise, the fifth installment in the Batman series soars on the basis of Christian Bale's incomparable Capped crusader -- he deserves to be a huge international star, Nolan's crisp (if a little too montage-friendly) direction, and his and David S. Goyer's witty script. It hardly seems possible, but Batman Begins demands a sequel, whereas the year's other blockbuster source narrative, The Revenge of the Sith, succeeded only in mercifully guiding its audience back to its Episode IV starting point.

Of course, Batman Begins is your prototypical event movie, monopolizing multiplex screens as it creates a panic not unlike the one that grips the Narrows in Nolan's pic. On the other hand, 5x2 is destined to a limited national release before it appears at only those video stores which are a bit more subtitle friendly. Closer in fate to the latter than the former is Miranda July's feature film debut Me and You and Everyone We Know, which christens the new IFC Film Center (at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Third Street in Lower Manhattan)this coming Friday. The winner of numerous prizes at both Sundance and Cannes, July's film reimagines Hal Hartley, exchanging a y-chromosome for an x. This is to say that Me and You... does not exactly cover new territory in its postmodern universe, though undoubtedly it will be welcomed as a fresh indie alternative to the dog days of the blockbuster season, which surely it is.

More than anything else, July's film demonstrates a tenderness for its characters, which the director democratically extends over her entire cast. In this way, July avoids the pitfall of the narcissistic actor-auteur -- that is to set his or her own character above their supporting players, intellectually and/or morally. Yet, it is not even this admirable characteristic that might be the film's greatest virtue, but rather Miranda July's own performance, which exudes a charm that is rare in any type of cinema, let alone a postmodern one that so often succumbs to bad faith (think the Coen Brothers).

Unfortunately for July's film, it does suffer a bit for its timing: Me and You and Everyone We Know possesses a mildly-creepy pedophiliac tenor. Now we're not talking Michael Jackson here, but in the days following the verdict you get my point. With that said, there is narrative justification for July's benign adoption of this trope, which it would seem redeems any hint of something uglier (which is only that, a hint). In the end, sex is never the motivation.

So what is the box office potential for Me and You and Everyone We Know? That of course remains to be seen, though surely it will not be hurt by its multiple prizes and what I suspect will be very good word of mouth. Both certainly are essential for any financial success that it may experience, as they are for most indie and mid-major motion pictures. As long as films of this scope -- and of 5x2's -- continued to be produced, they will depend greatly on the power-broking of the festival circuit. Likewise, your Batman Begins' will continue to be impervious to critical appraisal as their inherent cultural traction combined with obscene ad budgets will solidify their statuses as events.

Does this mean that film distribution is static? No, but in my judgment the future will not be characterized by a leveling, but rather by amplification of trends already current. Admittedly it was a Thursday afternoon screening six days after its premiere, but there were only nine other people in the Quad Theatre with me to see 5x2. Of these, at least three were senior citizens, meaning that they would have paid $7 max. That leaves, at most, seven people who paid the full $10. How can a theatre in Greenwich Village maintain the sort of overhead it does with such meager audiences? The answer is that it can't.

Now while the tendency might be thus to decry the injustices in the distribution process, this inviability might just pave the way for greater viewing opportunities for everyone -- not just those who live in the dozen or so US cities where one can expect to see your 5x2's. In my mind, on-line distribution is an inevitability: as long as there is a demand for art films, distribution will exist at some level. What on-line distribution affords is a minimal amount of overhead and a maximum audience. While the technology may or may not be there for all films to be made available thusly, it is going to happen because it is far and away the most economical system.

Consequently, one should expect the same thing to happen in film that has already happened in the music industry: increased fragmentation. As filmmaker and critic Chris Petit once speculated, in the future art films will be shared by e-mail. At the same time, for those more ambitious independent filmmakers, in my estimation, film festivals and critics will become even more important, as their roles as guides to the vast cosmos of independent film crystallize.

For those persons truly interested in the art of cinema, these are all good things, even though it shatters notions of cinema as a communal experience. Then again, when was the last time you interacted with someone you didn't know at a movie theatre? Of course one of the broader implications is the increasing isolation of recreation, but this isn't a factor that will shape the economics of film distribution. It's the cost efficiency of this system that will rule, which for anyone, who like myself may one day wish to make films closer to Ozon's or July's than to Nolan's, is a good thing. And for anyone who just likes to go to movies and pass a few hours experiencing visceral pleasure and eating popcorn, you know what, as long as there are millions of others who continue to share this desire, this will not change either. In fact, theatrical distribution may just become (or remain, I suppose) the prestige-guarantor for entertainment-first works, serving as little more than a tool to sell film downloads or DVDs -- however it will work -- just as festivals and critics will do the same for smaller films.

Yet, if Batman Begins suffers from an overdetermined application of psychoanalytic theory, this is about the only level where it proves lacking. Otherwise, the fifth installment in the Batman series soars on the basis of Christian Bale's incomparable Capped crusader -- he deserves to be a huge international star, Nolan's crisp (if a little too montage-friendly) direction, and his and David S. Goyer's witty script. It hardly seems possible, but Batman Begins demands a sequel, whereas the year's other blockbuster source narrative, The Revenge of the Sith, succeeded only in mercifully guiding its audience back to its Episode IV starting point.

Of course, Batman Begins is your prototypical event movie, monopolizing multiplex screens as it creates a panic not unlike the one that grips the Narrows in Nolan's pic. On the other hand, 5x2 is destined to a limited national release before it appears at only those video stores which are a bit more subtitle friendly. Closer in fate to the latter than the former is Miranda July's feature film debut Me and You and Everyone We Know, which christens the new IFC Film Center (at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Third Street in Lower Manhattan)this coming Friday. The winner of numerous prizes at both Sundance and Cannes, July's film reimagines Hal Hartley, exchanging a y-chromosome for an x. This is to say that Me and You... does not exactly cover new territory in its postmodern universe, though undoubtedly it will be welcomed as a fresh indie alternative to the dog days of the blockbuster season, which surely it is.

More than anything else, July's film demonstrates a tenderness for its characters, which the director democratically extends over her entire cast. In this way, July avoids the pitfall of the narcissistic actor-auteur -- that is to set his or her own character above their supporting players, intellectually and/or morally. Yet, it is not even this admirable characteristic that might be the film's greatest virtue, but rather Miranda July's own performance, which exudes a charm that is rare in any type of cinema, let alone a postmodern one that so often succumbs to bad faith (think the Coen Brothers).

Unfortunately for July's film, it does suffer a bit for its timing: Me and You and Everyone We Know possesses a mildly-creepy pedophiliac tenor. Now we're not talking Michael Jackson here, but in the days following the verdict you get my point. With that said, there is narrative justification for July's benign adoption of this trope, which it would seem redeems any hint of something uglier (which is only that, a hint). In the end, sex is never the motivation.

So what is the box office potential for Me and You and Everyone We Know? That of course remains to be seen, though surely it will not be hurt by its multiple prizes and what I suspect will be very good word of mouth. Both certainly are essential for any financial success that it may experience, as they are for most indie and mid-major motion pictures. As long as films of this scope -- and of 5x2's -- continued to be produced, they will depend greatly on the power-broking of the festival circuit. Likewise, your Batman Begins' will continue to be impervious to critical appraisal as their inherent cultural traction combined with obscene ad budgets will solidify their statuses as events.

Does this mean that film distribution is static? No, but in my judgment the future will not be characterized by a leveling, but rather by amplification of trends already current. Admittedly it was a Thursday afternoon screening six days after its premiere, but there were only nine other people in the Quad Theatre with me to see 5x2. Of these, at least three were senior citizens, meaning that they would have paid $7 max. That leaves, at most, seven people who paid the full $10. How can a theatre in Greenwich Village maintain the sort of overhead it does with such meager audiences? The answer is that it can't.

Now while the tendency might be thus to decry the injustices in the distribution process, this inviability might just pave the way for greater viewing opportunities for everyone -- not just those who live in the dozen or so US cities where one can expect to see your 5x2's. In my mind, on-line distribution is an inevitability: as long as there is a demand for art films, distribution will exist at some level. What on-line distribution affords is a minimal amount of overhead and a maximum audience. While the technology may or may not be there for all films to be made available thusly, it is going to happen because it is far and away the most economical system.

Consequently, one should expect the same thing to happen in film that has already happened in the music industry: increased fragmentation. As filmmaker and critic Chris Petit once speculated, in the future art films will be shared by e-mail. At the same time, for those more ambitious independent filmmakers, in my estimation, film festivals and critics will become even more important, as their roles as guides to the vast cosmos of independent film crystallize.

For those persons truly interested in the art of cinema, these are all good things, even though it shatters notions of cinema as a communal experience. Then again, when was the last time you interacted with someone you didn't know at a movie theatre? Of course one of the broader implications is the increasing isolation of recreation, but this isn't a factor that will shape the economics of film distribution. It's the cost efficiency of this system that will rule, which for anyone, who like myself may one day wish to make films closer to Ozon's or July's than to Nolan's, is a good thing. And for anyone who just likes to go to movies and pass a few hours experiencing visceral pleasure and eating popcorn, you know what, as long as there are millions of others who continue to share this desire, this will not change either. In fact, theatrical distribution may just become (or remain, I suppose) the prestige-guarantor for entertainment-first works, serving as little more than a tool to sell film downloads or DVDs -- however it will work -- just as festivals and critics will do the same for smaller films.

No comments:

Post a Comment