Either way, the inclusion of Francesco Vezzoli's Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal's Caligula (2005) speaks to the aesthetic paucity of the Biennial endeavor.

First there is the trailer's credited writer and its namesake, Gore Vidal: before his participation in such unremittingly trashy exercises as Myra Breckinridge (novel) and the aforementioned Caligula (screenplay), Vidal was responsible for some of the greatest dross ever to grace the silver screen -- he penned Suddenly, Last Summer and Ben-Hur in a single inglorious year (1959). Second, there is the fact that a trailer, an advertisement for a film -- albeit for a non-existent remake -- is somehow supposed to constitute noteworthy art. The best trailers either a) tell us what a film is about and/or b) convey the film's mood or a feeling for the film that will c) encourage the spectator to want to see the film. This is their function. A fictitious trailer will continue to do a) and/or b), producing irony when thoughts of c) are broached. Are we really being told that this experience is as important to us as are our traditional inquiries into who we are, where we come from and where we are going, or at least to questions concerning the ontological status of the art -- and no, a flaccid critique of "capitalism" or "media" or what have you does not an engagement of these questions make -- or is it that no one is willing to ask these questions any more? Whichever way you look at, Vezzoli and Vidal's inclusion in the Biennial is troubling.

Fortunately, not all the video art in Day for Night was nearly this inelegant and insubstantial.

This year's best in show, regardless of medium (and by a large margin at that), was Pierre Huyghe's A Journey That Wasn't (2005), "a travelogue/ fairy tale/ performance of immense beauty and mystery," as it has been described by its Termite Art advocate, R. Emmet Sweeney. A Journey That Wasn't alternates super 16 and HD footage of Antarctica and Central Park's Wollman Rink, where Huyghe staged a performance of his voyage in October 2005, backed by a 42-piece orchestra. The expedition itself centers upon the attempted discovery of a rare albino penguin, which Huyghe's film captures in the closing minutes. I mention this lest any of its spectators missed the penguin's appearance, which I should also mention matters neither to one's assessment of the work's quality nor even to the viewer's experience of the work. The fact is that as a film intended for gallery rather than theatrical exhibition, The Journey That Wasn't is to be (and most certainly will be) viewed in segments that often commence after the film has begun and conclude before the film is over -- in other words as its spectators walk into and out of its exhibition space.

This year's best in show, regardless of medium (and by a large margin at that), was Pierre Huyghe's A Journey That Wasn't (2005), "a travelogue/ fairy tale/ performance of immense beauty and mystery," as it has been described by its Termite Art advocate, R. Emmet Sweeney. A Journey That Wasn't alternates super 16 and HD footage of Antarctica and Central Park's Wollman Rink, where Huyghe staged a performance of his voyage in October 2005, backed by a 42-piece orchestra. The expedition itself centers upon the attempted discovery of a rare albino penguin, which Huyghe's film captures in the closing minutes. I mention this lest any of its spectators missed the penguin's appearance, which I should also mention matters neither to one's assessment of the work's quality nor even to the viewer's experience of the work. The fact is that as a film intended for gallery rather than theatrical exhibition, The Journey That Wasn't is to be (and most certainly will be) viewed in segments that often commence after the film has begun and conclude before the film is over -- in other words as its spectators walk into and out of its exhibition space.

Corresponding to this variation in form, The Journey That Wasn't articulates its content through a frequent repetition of leitmotifs, rather than via a more conventional story arc. Specifically, it is the documentary facts of each, both the topographical details of the spaces and also the spectacle of human -- and animal -- presence. Resulting is a work that both emphasizes the Biennial's stated preoccupation with reflexivity, and more subtly, the texture and tactile cold of the environs. Whereas Huyghe captures the placid black surfaces, floating snow-packed isles and brutal cold of a liquid that barely surpasses 32º F, with a conscienciousness rivaling Flaherty or the recent landscape documentaries of James Benning (13 Lakes and Ten Skies, both 2004), an indeterminacy surrounds his mist-shrouded Central Park reproductions: is it a crisp autumn evening or is it more unseasonnal; and does the water have any discernable cooling effect of its own? In short, the artifical setting lacks the tactile precision of the natural locale. All of this is to say that The Journey That Wasn't utilizes its form to stimulate the sensorial memory of its spectator (in responding to the work's tactility) while asking he or she to consider their experience of viewing the film, which is simulated in the Central Park reproduction; the Whitney spectator, like the Wollman rink participant, views an aesthetic interpretation of an Antarctic expedition.

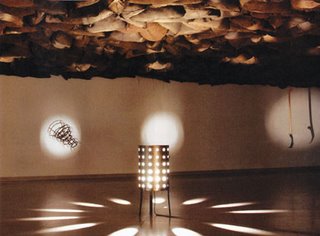

Apart from the moving image, another of the more compelling reconfigurations of form belonged to Urs Fisher, who attached burning candles to a pair of swinging pendulums, thereby charting its invisible path on the floor beneath. (Fisher's sculpture fills a space confined by cut-out walls that similarly annunciate the otherwise unseen.) Likewise, Elaine Sturtevant's reproduction of Marcel

Duchamp's epochal display of "found" objects translates a discrete space through a specific aesthetic idea -- that her feeling for these pieces constitutes as much of an artistic expression as did his -- which nevertheless succumbs to the same cynicism of the original, even if it avoids the joking quality of both Duchamp's instillation and most of the other work contained in Day for Night.

Duchamp's epochal display of "found" objects translates a discrete space through a specific aesthetic idea -- that her feeling for these pieces constitutes as much of an artistic expression as did his -- which nevertheless succumbs to the same cynicism of the original, even if it avoids the joking quality of both Duchamp's instillation and most of the other work contained in Day for Night.If there is an overarching weakness displayed in this year's biennial, it is that same pestering rash that has inflicted the Western art world since the end of the modernist age: irony. Everything has to have a punch-line. The artist is forever superior to his or her subject. Humility does not exist in postmodern art. Whatever this portends, western art has not been able to find its way since modernism first began to lose its momentum. If nothing else, the Whitney Biennial offers us a glimpse into contemporary art's most celebrated placeholders.