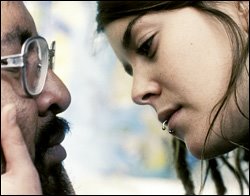

Following the shocking opener, Reygadas introduces us to his hero Marcos, whom we soon learn -- in an almost off-handed off-camera revelation -- has just been involved in the kidnapping of a baby who tragically died during the affair. This point, however, garners far less narrative time than the fellatio or than Reygadas' seemingly ethnographic interest in the Mexico City subway tunnels where Marcos' wife sells her wares.

However, it is not a third-world tourist impulse that animates Reygadas in so precisely detailing the latter, but it is rather social commentary, particularly when Marcos' subsequent experiences are compared to those of his female employer, Ana, as he drives the young woman home from the airport, through the tree-lined boulevards of her leafy suburb. Importantly, Reygadas lingers on both the public space of the metro system and the private space of the automobile to convey the sense in which the dead time for the country's working poor is characteristically chaotic, whereas comfort defines these moments for the rich.

However, it is not a third-world tourist impulse that animates Reygadas in so precisely detailing the latter, but it is rather social commentary, particularly when Marcos' subsequent experiences are compared to those of his female employer, Ana, as he drives the young woman home from the airport, through the tree-lined boulevards of her leafy suburb. Importantly, Reygadas lingers on both the public space of the metro system and the private space of the automobile to convey the sense in which the dead time for the country's working poor is characteristically chaotic, whereas comfort defines these moments for the rich.In a telling moment of social incongruity, Ana asks Marcos a question and then quickly interrupts him once her boyfriend is free again to speak with her on her cell phone. Yet, if Ana does treat Marcos as an employee who is of less importance than even the most trivial incidents in her own life, she does seem to maintain a certain fondness for and trust in Marcos, whom she asks to take her to a brothel where evidently she works in secret. There, Marcos, refuses the pleasures of a young prostitute insisting that Ana forced him to come. Ana then interrogates Marcos about his feelings for her, but drops it when it becomes clear how he feels.

At this point, the opening salvo increasingly looks as if it may exist outside the time of the film narrative altogether, be it as a representation of his fantasy, or more compellingly, as a purveyor of formal and social meaning, at once illuminating Reygadas' post-Kiarostami tendency to constrict the visual field while creating an expansive aural space, even as his lowly mestizo character is pleasured by a woman of higher social standing whom we assume would never do something like this in real life. In other words, Reygadas uses his fellatio as a socially-leveling device. There is indeed something intriguing to this latter reading, even if Reygadas does have the pair engage in intercourse later in the film. Then again, this simulated sexual act is presented on screen in long take, whereas Reygadas masks this same activity between Marcos and his equally unattractive wife.

Speaking of this latter sex act, when it concludes, Reygadas moves his camera to disclose an image of Christ over the couple's bed, even as their heavy-breathing continues. This apparent visual joke, far from a throw away, in fact distills a key component of the director's vision: the idea of ecstasy (as in Bernini's St. Theresa). Following the pilgrimage that Marcos ultimately joins, seemingly in a desperate search for forgiveness, Reygadas closes his film with the second fellatio scene, which in this case shows Marcos grinning for the first time and hovering over Ana in a position of power. As such, Reygadas conflates the transcendence inherent in both religious devotion and sexual fulfillment, in a fashion that one could see as congruent with the noted trend in baroque figuration. Moreover, the pilgrimage itself follows a definitive conflation of sex and violence that seems to situate Reygadas in a tradition in Mexican filmmaking that also includes two of its most accomplished directors, Luis Buñuel and Arturo Ripstein.

Speaking of this latter sex act, when it concludes, Reygadas moves his camera to disclose an image of Christ over the couple's bed, even as their heavy-breathing continues. This apparent visual joke, far from a throw away, in fact distills a key component of the director's vision: the idea of ecstasy (as in Bernini's St. Theresa). Following the pilgrimage that Marcos ultimately joins, seemingly in a desperate search for forgiveness, Reygadas closes his film with the second fellatio scene, which in this case shows Marcos grinning for the first time and hovering over Ana in a position of power. As such, Reygadas conflates the transcendence inherent in both religious devotion and sexual fulfillment, in a fashion that one could see as congruent with the noted trend in baroque figuration. Moreover, the pilgrimage itself follows a definitive conflation of sex and violence that seems to situate Reygadas in a tradition in Mexican filmmaking that also includes two of its most accomplished directors, Luis Buñuel and Arturo Ripstein.However, it is not simply these themes that find their way into these concluding gestures -- both the violence and the sex act -- but it is moreover Reygadas' arguably radical view of a reconstituted Mexican society. The intimation may be that a violent overthrow of class structures is required, but in the universe of Battle in Heaven a little fellatio would seem to suffice.

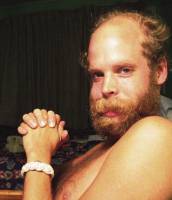

Kelly Reichardt's Rotterdam prize-winner Old Joy, which will play at New York's Walter Reade theatre as part of their 'New Directors' series on March 21st (and which should manage some form of distribution thereafter, one would hope), begins with the image of a bird perched on a gutter followed by a series of shots of a man, covered in ants, meditating in the grass. In other words, its opening passage is a whisper to Reygadas' scream, even if similarities abound elsewhere. For one, both films share a documentarian concern for the non-fictional locations of their narratives.

In the case of Old Joy, this is (lower-middle class) Portland and its mountainous environs: roadsides and passing storm cloud formations seem to attract nearly as much attention as the strained interaction of the two 'old friend' leads, Mark (Daniel London) and Kurt (Palace Music frontman Will Oldham).

Backtracking for the moment, the spare narrative of Old Joy concerns Mark and Kurt's overnight camping trip, with a visit to a local hot springs to follow the next day. Throw in Mark's pregnant partner, an avowedly liberal radio talk show, and a diner visit in the morning and one has the totality of Old Joy's narrative. Nevertheless, Reichardt's narrative demands nothing further as she needs little more than a quick shoulder rub and an arm dropping into the hot spring water to say everything that we would ever need to know about the past, present and future of their friendship. Old Joy demonstrates an admirable economy, which along with its contemplative tone distinguishes it from the vast majority of "indie" cinema.

Then again it is not these qualities alone that recommend Reichart's film, even if she does mildly contaminate the film's understated poignancy with a final gesture consistent with the film's liberal humanist rhetoric. Old Joy importantly manifests a genuine nostalgia for Gen X's heyday -- the Slacker to Reality Bites years -- making it (along with the undeniably elegiac Before Sunset [2005]) as one of the first works to long for this not-so-long ago 'golden age.' However, what makes this film particularly significant on this front, given the liberal values espoused by Kurt and the left-wing, call-in talk show that Mark listens to, is the speed in which this impression has been reached by Generation X's left-of-center constituency (which importantly was always far smaller than their parents'). Evidently an era that made Eddie Vedder its mouthpiece wasn't entirely successful at changing the world after all? All kidding aside, Old Joy represents an important next step in 'Gen X' cinema.

No comments:

Post a Comment