The Film Society at Lincoln Center's From the Tsars to the Stars: A Journey Through Russian Fantastik Cinema does precisely what repertory cinema in the age of DVD ought to do: expose audiences to large numbers of otherwise unavailable titles, selected from a historical moment that remains mostly unknown to moviegoers. Karen Shakhnazarov's Zero City (1988) is in this way representative of the series as a whole, representing neither the salad days of the Soviet silent cinema nor the period of the Thaw and the subsequent emergence of a poetic counter-cinema in the works of Sergei Paradjanov and Andrei Tarkovsky. Instead, Zero City is very much a product of its own, slightly overlooked moment -- the late perestroika era, of which Kira Muratova's The Asthenic Syndrome (1989) and Aleksandr Sokurov's The Second Circle (1990) are the better-known masterpieces -- with its preminition of the Soviet Union's disintegration twined with an ambivalence toward the nation's post-communist future. Shakhnazarov's picture, like Muratova's, relies heavily upon the (il)logic of the absurd and trades heavily upon the creation of images of striking visual beauty, which to be sure would reach its stylistic apogee a decade later in Aleksei German's virtually incomprehensible Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998).

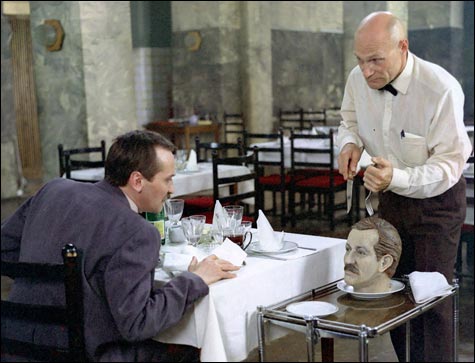

As an earlier step in this tradition and not that latter point of extremum, however, Zero City does paint a somewhat clearer portrait of both Soviet administrative disfunction, in the not-so-with-it provincial office replete with its very own nude secretery -- unbenounced to the boss -- and the trans-Atlantic crassness that seems to infect both Shakhnazarov's home country and its Cold War opponent -- which the director dissects first in the oddly out-of-place waxworks museum and later in a hotel meeting that makes careful reference of both anachronistic American rock-and-roll and even more out-dated Soviet song.

If anything, Zero City has the flavor of a David Lynch-Theo Angelopoulos mash-up, even as it maintains a strongly allegorical, and therefore late Soviet narrative: particularly revealing is the tree, whose branches were said to have granted the Russian state's greatest leader their might, but whose limbs have become startlingly brittle. Indeed, if there is a single image that can be said to sum up the Soviet Union's subsequent collapse in the cinema of that still relatively nigh era, it is this twilight visual.

Neither as epochal as Zero City nor as little-known internationally, Andrei Tarkovsky's crowning masterpiece Stalker (1979) is likewise being screened as part of the Russian Fantastik series, before receiving its long-awaited US DVD release from Kino International -- in a beautiful new print supplied by Russian distributor Ruscico -- on the third of October. Yet, if Stalker fails to summarize an era, it nonetheless impresses mightly with the courage of its critique of the then current political realities of Soviet life, and particularly its figuration of religious supression: it is no coincidence that Stalker is Tarkovsky's last Soviet film before seeking political refuge in Italy. To be specific, Stalker allegorizes the process of spiritual journey in a state that has forbidden an equivalent form of knowledge, which in Tarkovsky's film is translated into the space known as "The Zone."

Stalker opens with the titular lead leaving his wife and crippled daughter to lead two seekers to the aforementioned location (behaving as though he is answering the New Testament call to leave everything and follow Christ). His fellow travelers are referred to merely as Professor (a physicist) and Writer, thereby providing the film with unmistakable metaphorical grist for its narrative mill. The stalker subsequently leads the pair under the noses of armed military guards into the so-called Zone, at which point Tarkovsky transforms his palette from a sepia monochrome to full color. If this shift is the most obviously totem of Tarkovsky's stylistic transformation, it should be likewise noted that the Zone itself is filled with tall grasses that have overtaken the military hardware that is scattered throughout the space. This is a post-apocalyptic world to be sure, but one in which nature has begun to reclaim its place among the symbols of desolate industrial landscape. Of course, Tarkovsky's configuration of the space thusly not only fits his narrative discernment of the sepia industrial wasteland and the color-filled Zone, but it offers an external expression of the human beings in-born quest for spiritual fulfillment and its inability to be supressed through the rational ordering of human life within the socialist state -- a sort of reverse Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

Once there, it soons become evident that neither passenger possesses the purity of motives that the stalker had hoped they would: the Professor reveals his desire to destroy the Zone, and the Writer instinctively collaborates. In this way, Tarkovsky seems to suggest the Soviet Union's systematic elimination of religious life and the complicity of his country's artists (Eisenstein and October [1928] for example) in discouraging faith -- often by the barrel of a gun, to be sure. As such, Stalker reveals a crisis of faith certainly, but it is one shared by his fellow countrymen to the exclusion of the film's lead, and implicitly Tarkovsky, both of whom can only despair at its prospect (though, importantly, Stalker does suggest that there may be hope for the next generation, which the director establishes via the stalker's daughter's telepathic powers).

That one can read Tarkovsky in Stalker, moreover, is an important element of both the film's narrative structure, as well as its style: at one point the stalker himself argues that purpose of life is to create art, through which one can't help read the author's point-of-view. Likewise, even the picture's style, as has been suggested, indicates the conscious agency of a creator artist. As an example, take one of the film's opening long takes -- Tarkovsky's preferred means of constructing the time and space of his narratives -- wherein the titular Stalker exits frame and then reappears immediately in front of Tarkovsky's camera. In so doing, the camera seems to announce its presence in Stalker, as said character gets too close to the camera to maintain the illusion of an unembellished depth-of-field, even if he moves unawares through the space of the film. Similarly, the director's use of a zoom lens and even two seperate instances in which a character looks at the camera, in the second the character addresses it verbally, further confirms the interventionism of the director's practice, and ultimately the self-consciousness of his directorial style.

Even so, if Stalker can be read both as a direct condemnation of the Soviet Union's supression of religious expression (and the subsequent barrenness of spiritual life in that state) as well as an affirmation of art's privileged status, and particularly of its importance to the director himself, Tarkovsky language often remains analogical and his symbolism personal: what for instance is to be made of the profusion of water throughout the Zone? In this way, one might position Stalker within a tradition parallel to the absurdist school noted at the outset, noteworthy for its poetic language rather than its illogical impulse.

As an earlier step in this tradition and not that latter point of extremum, however, Zero City does paint a somewhat clearer portrait of both Soviet administrative disfunction, in the not-so-with-it provincial office replete with its very own nude secretery -- unbenounced to the boss -- and the trans-Atlantic crassness that seems to infect both Shakhnazarov's home country and its Cold War opponent -- which the director dissects first in the oddly out-of-place waxworks museum and later in a hotel meeting that makes careful reference of both anachronistic American rock-and-roll and even more out-dated Soviet song.

If anything, Zero City has the flavor of a David Lynch-Theo Angelopoulos mash-up, even as it maintains a strongly allegorical, and therefore late Soviet narrative: particularly revealing is the tree, whose branches were said to have granted the Russian state's greatest leader their might, but whose limbs have become startlingly brittle. Indeed, if there is a single image that can be said to sum up the Soviet Union's subsequent collapse in the cinema of that still relatively nigh era, it is this twilight visual.

Neither as epochal as Zero City nor as little-known internationally, Andrei Tarkovsky's crowning masterpiece Stalker (1979) is likewise being screened as part of the Russian Fantastik series, before receiving its long-awaited US DVD release from Kino International -- in a beautiful new print supplied by Russian distributor Ruscico -- on the third of October. Yet, if Stalker fails to summarize an era, it nonetheless impresses mightly with the courage of its critique of the then current political realities of Soviet life, and particularly its figuration of religious supression: it is no coincidence that Stalker is Tarkovsky's last Soviet film before seeking political refuge in Italy. To be specific, Stalker allegorizes the process of spiritual journey in a state that has forbidden an equivalent form of knowledge, which in Tarkovsky's film is translated into the space known as "The Zone."

Stalker opens with the titular lead leaving his wife and crippled daughter to lead two seekers to the aforementioned location (behaving as though he is answering the New Testament call to leave everything and follow Christ). His fellow travelers are referred to merely as Professor (a physicist) and Writer, thereby providing the film with unmistakable metaphorical grist for its narrative mill. The stalker subsequently leads the pair under the noses of armed military guards into the so-called Zone, at which point Tarkovsky transforms his palette from a sepia monochrome to full color. If this shift is the most obviously totem of Tarkovsky's stylistic transformation, it should be likewise noted that the Zone itself is filled with tall grasses that have overtaken the military hardware that is scattered throughout the space. This is a post-apocalyptic world to be sure, but one in which nature has begun to reclaim its place among the symbols of desolate industrial landscape. Of course, Tarkovsky's configuration of the space thusly not only fits his narrative discernment of the sepia industrial wasteland and the color-filled Zone, but it offers an external expression of the human beings in-born quest for spiritual fulfillment and its inability to be supressed through the rational ordering of human life within the socialist state -- a sort of reverse Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

Once there, it soons become evident that neither passenger possesses the purity of motives that the stalker had hoped they would: the Professor reveals his desire to destroy the Zone, and the Writer instinctively collaborates. In this way, Tarkovsky seems to suggest the Soviet Union's systematic elimination of religious life and the complicity of his country's artists (Eisenstein and October [1928] for example) in discouraging faith -- often by the barrel of a gun, to be sure. As such, Stalker reveals a crisis of faith certainly, but it is one shared by his fellow countrymen to the exclusion of the film's lead, and implicitly Tarkovsky, both of whom can only despair at its prospect (though, importantly, Stalker does suggest that there may be hope for the next generation, which the director establishes via the stalker's daughter's telepathic powers).

That one can read Tarkovsky in Stalker, moreover, is an important element of both the film's narrative structure, as well as its style: at one point the stalker himself argues that purpose of life is to create art, through which one can't help read the author's point-of-view. Likewise, even the picture's style, as has been suggested, indicates the conscious agency of a creator artist. As an example, take one of the film's opening long takes -- Tarkovsky's preferred means of constructing the time and space of his narratives -- wherein the titular Stalker exits frame and then reappears immediately in front of Tarkovsky's camera. In so doing, the camera seems to announce its presence in Stalker, as said character gets too close to the camera to maintain the illusion of an unembellished depth-of-field, even if he moves unawares through the space of the film. Similarly, the director's use of a zoom lens and even two seperate instances in which a character looks at the camera, in the second the character addresses it verbally, further confirms the interventionism of the director's practice, and ultimately the self-consciousness of his directorial style.

Even so, if Stalker can be read both as a direct condemnation of the Soviet Union's supression of religious expression (and the subsequent barrenness of spiritual life in that state) as well as an affirmation of art's privileged status, and particularly of its importance to the director himself, Tarkovsky language often remains analogical and his symbolism personal: what for instance is to be made of the profusion of water throughout the Zone? In this way, one might position Stalker within a tradition parallel to the absurdist school noted at the outset, noteworthy for its poetic language rather than its illogical impulse.

No comments:

Post a Comment