"All arts are founded on man's presence; only in photography do we enjoy his absence."

-Andre Bazin

Tacita Dean's Kodak (2006) joins James Benning's Ten Skies (2004) and Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub's These Encounters of Theirs (2006) as one of the finest new films to screen in New York thus far this year. Add to these works of the experimental (primarily non-narrative) cinema Film Comments Selects highlight Colossal Youth (Pedro Costa, 2006) and the structuralist-influenced April opening Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006), and one begins to wonder whether narrative cinema isn't beginning to fall further behind its avant-garde and poetic counterparts qualitatively. After such a lackluster year for Hollywood, such a claim does not seem as far-stretched as it might otherwise. Even the mid-majors have shown this turn with Michel Gondry's The Science of Sleep (2006). Of course, none of those films listed at the outset, in addition to Costa's, have or ever will receive anything approaching commercial distribution.

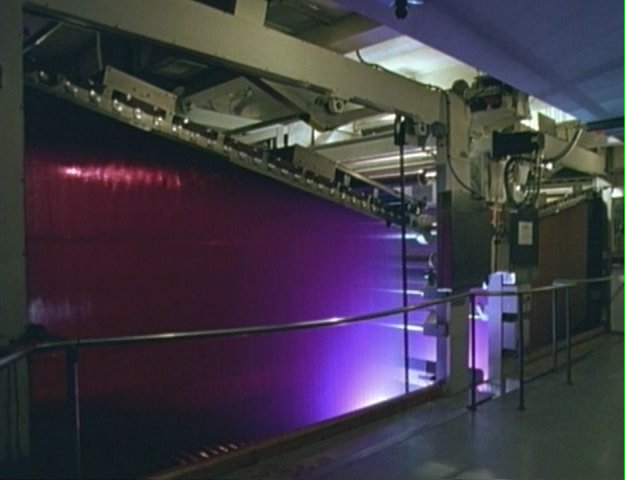

Fortunately, the Guggenheim New York is currently screening two of Tacita Dean's 16mm works, including the 40-plus minute Kodak, as part of its supplementary exhibition, The Hugo Boss Prize 2006: Tacita Dean. Kodak features footage of one of the eponymous film company's factories shot after Dean learned that this manufacturer of her 16mm medium was slated to close. Utilizing that same format, Kodak makes an argument for her medium's specificity and superiority over digital technologies in its registration of sensuous tones (particularly yellows, royal blues, turquoise/sea-greens and pink-tinted purples) in exceedingly low light. Dean's spare lighting often adorns empty corridors, which draw attention to film's post-human character -- that is as an indexical medium. This quality is similarly evident in Kodak's emphasis on the translucent material, which likewise underscores the medium's fragility. Indeed, this is the ultimate meaning that inheres within Kodak: namely, of a medium that is ceasing to exist, both in its lack of production and in the instability of the format itself. This eulogistic sense is suggested further in the concluding images of factory waste on the wet mill floor.

While the Tacita Dean exhibit occupies only a single room within the museum, the remaining non-permanent galleries are devoted to the epic Spanish Painting from El Greco to Picasso: Time, Truth, and History. As I may still write on the exhibition elsewhere, my comments will remain of necessity cursory. Suffice it to say of the enormous showcase, then, that while Spanish Painting does not break new ground, it does have the virtue of clarifying the unity of the Spanish visual tradition, and particularly the titular Picasso's self-conscious revisionism vis-a-vis his national context. In the end, if Picasso's art demonstrates the greatest dexterity, Goya's emerges as perhaps the most influential, Velázquez's the ultimate achievement in his nation's plastic tradition and El Greco's and Miro's the most respectively singular. It is worth noting that the exhibition is arranged by theme with many of the newer works (especially Picasso's) hanging beside those pieces that served as inspiration, either directly or indirectly.

For someone who is better versed in El Greco, Goya and Picasso, the opportunity to see such a large number of Velázquez's again -- many of which are on loan from the Prado -- serves to reinforce his preeminent stature, at least in this author's opinion: that is, as one of the oil medium's greatest practitioners, perhaps even the equal of Rembrandt himself. To be terse, Velázquez appears in Spanish Painting to be his art's greatest humanist: in the superlative "Don Sebastián de Morra" (ca. 1643-4) for example, the painter's representation of the little person secures the full weight of his subject's sadness, deriving as it does from his physical limitations -- both his height and his meaty hands. (A second similarly socially-themed highlight is Goya's "The Young Woman (The Letter)," after 1812, which limns the aristocratic subject concretely, while her servant and the workers behind her are all represented without this same clarity.) That is, Velázquez -- and Goya -- emphasize the social, whereas Rembandt's focus is the spiritual. To put it differently, Velázquez's subjects lack the souls that are the focus of his Dutch counterpart's art. Again, for Velázquez, it is their position within a social system and the impact that this has on their psychology -- to say nothing of his preoccupation with their garment's textures (Velázquez's painting, at its most assured, approaches a second sense, that of the creation of touch) and the medium itself, which all combine to forge the essence of his art.

Fifteen blocks to the south, The Whitney Museum of American Art is currently exhibiting the "anarchitecture" of Gordon Matta-Clark. Again, to be brief, Matta-Clark, son of Surrealist painter Roberto Matta, is perhaps best known for his incisions cut into abandoned or condemned structures, such as a pair of late 17th century homes (in "Conical Intersect") situated beside Paris's Centre Pompidou, or his 1974 "Splitting" where he does exactly that to a one-family home. In summary, Matta-Clark's art aids his spectator in securing a new perspective in viewing familiar locations, while offering substantive social and psychological ramifications: to the former, they assist us in understanding how people live together in cities, while the latter indicates both a formalization of Matta-Clark's broken home, and even more compellingly, his twin brother's suicide.

In terms of his media, since his art is by its definition ephemeral -- buildings immediately prior to their demolishing -- Matta-Clark portrayed his sites in both photographs and films. In so doing, Matta-Clark offers an analogy between his activity ("to clarify our personal awareness of place") and the process of representing the three-dimensional in two dimensions (namely, of finding a method to explode the spatial barriers inherent on said format). Thus, there is a rigor to match the artist's ambition, marking Matta-Clark as an exceedingly significant post-war American artist.

2 comments:

A fascinating post, Michael. I always appreciate reading your insights and hearing about all the things I miss by living in Milwaukee! Oh well, at least we got the Francis Bacon exhibition.

Thank you, Nathaniel... and I would say that a Francis Bacon exhibition is nothing to scoff at.

Post a Comment