Although Roberto Rossellini was indisputably one of the most influential of European directors, the fact that his influence was founded upon a philosophical or conceptual attitude rather than upon the imitation of stylistic devices or thematic preoccupations has meant that Anglo-American film historians in particular tend to pay little more than lip service to his achievement, when not ignoring it altogether. Yet such indifference constitutes a major injustice not merely to a director who redefined the parameters of the cinema but to one of the supreme "documenters," in any art form, of the latter half of the 20th century.

-Gilbert Adair

Roberto Rossellini is one of those curious figures in world cinema who seems to generate more respect than admiration. As Adair accurately points out, the reverence typically paid to the director is little more than tokenism. Certainly, his realist aesthetic -- location shooting, natural light, non-professional actors, longer-duration takes -- has benefited filmmakers of sparse means the world over. He is remembered as a figure of undeniable historical significance without being thought of as the equal to directors of a similar influence (such as Griffith, Renoir, Welles, Bresson, Godard). He certainly lacks the devotion many hold for his best-known countrymen, from Fellini to Antonioni to Bertolucci, among others. However, I would submit that he is at once their superior and the greatest of all Italian directors, without even making any allowance for his firm place in film history. This is to say that his corpus speaks for itself, outside of history, as one of the most beautiful and inspired that the medium has yet seen.

Yet, again he is underestimated. The reason for this, it would seem to me, is that Rossellini's style is too often considered for its historical circumstances, its facility for assimilation, and even for what he expresses through this style (or less opaquely, his themes) rather than for what this style says about the director's viewpoint. Indeed, it is in an examination of its conceptual genesis that a unity emerges to Rossellini's corpus, marking him as one of the medium's best.

Specifically, it seems to me that the key to appreciating Rossellini rests in his epistemological ideas. For Rossellini, the truth is evident on the surface of things. From his early, immediately post-war films (Rome, Open City [1945], Paisa [1946], Germany, Year Zero [1948]) to his Bergman cycle (including Stromboli [1950], Voyage in Italy [1953] and Fear [1954]), his historical recreations (The Flowers of St. Francis [1950] and The Rise to Power of Louis XIV [1966] among others) and more proper documentaries (such as India [1958]), what marks his entire body of mature work is a faith in humankind's perception of truth. Take the somewhat forgotten, small masterwork Fear: throughout the picture, Bergman's character attempts to conceal the truth of an adulterous affair. However, her body language belies the secret she is attempting to hide -- at one point her blackmailer asks rhetorically why she blushes, why her hands trembled and why she was so quick to give away her money. In other words, in spite of a shared Catholic faith with Robert Bresson, Rossellini departs from the Frenchmen (as well as from such directors as Michelangelo Antonioni, Wong Kar-wai, and even Eric Rohmer in Triple Agent [2004]) in the his view that psychology is discernible in gesture.

As it has been claimed, this basic understanding of the comprehensibility of truth is not limited in fact to the psychologically-intensive Bergman cycle, but manifests itself throughout his ouevre. The post-war texts offer their morals within the context (another key theme in Rossellini) of a war-ravaged Europe. In seeing the condition of Germany in the 1948 film, one understands the despair of the child protagonist. Surface reality discloses truth. Similarly, The Flowers of St. Francis, perhaps his greatest work, shows (key theme number three) the basic rhythm of a long-since extinct life -- a life lived absent of any goals other than the service of the Lord -- which as such reveals Christianity's distinct understanding of time; less abstractly, India proposes that its presentation of Indian life is sufficient to reveal essential truths of the nation.

In this basic understanding of epistemology, I would argue, Rossellini shows himself to be an artist seeking a form to express his ideas, not simply the innovator of a technique born of historical circumstance. It is in this consistency of viewpoint, manifesting itself in his form, that the beauty of his work becomes clear. Rossellini's cinema deserves to be appreciated not only for its historical value, but indeed for the beauty of its expression of content. In this lies its grace.

Wednesday, August 31, 2005

Friday, August 19, 2005

New Film: The 40-Year-Old Virgin & Grizzly Man

Judd Apatow's The 40-Year-Old Virgin does not hit screens without a certain amount of promise: after all, Apatow was the creator of the highly underrated television series "Undeclared" (2001), the follow-up to the exceptional "Freaks and Geeks" (1999), where he likewise worked in the capacities of both writer and director. Moreover, The 40-Year-Old Virgin seems to represent the belated break-through of its undeniably talented lead, Steve Carell, who has thus far shown brightest in his supporting roles in Anchorman (2004), as a correspondent on "The Daily Show," and most recently as America's answer to David Brent in NBC's remake of "The Office." While the latter may in fact come to fruition, The 40-Year-Old Virgin suffers most from its authorial viewpoint. To back-track, "Undeclared" is an under-appreciated series, to be sure, which hopefully will be remedied by its recent release on DVD, but this does not mean that it is without its deficiencies. Particularly, "Undeclared," like The 40 Year-Old-Virgin, showcases a lack of moral assessment when it comes to the sexual conduct of its character. If there is an ethos in Apatow's world -- of which "Freaks and Geeks" can be excluded on the basis that it is ultimately Paul Feig's creation -- it is that people will have sex, period. There is no moral reckoning based on abstract principles.

Judd Apatow's The 40-Year-Old Virgin does not hit screens without a certain amount of promise: after all, Apatow was the creator of the highly underrated television series "Undeclared" (2001), the follow-up to the exceptional "Freaks and Geeks" (1999), where he likewise worked in the capacities of both writer and director. Moreover, The 40-Year-Old Virgin seems to represent the belated break-through of its undeniably talented lead, Steve Carell, who has thus far shown brightest in his supporting roles in Anchorman (2004), as a correspondent on "The Daily Show," and most recently as America's answer to David Brent in NBC's remake of "The Office." While the latter may in fact come to fruition, The 40-Year-Old Virgin suffers most from its authorial viewpoint. To back-track, "Undeclared" is an under-appreciated series, to be sure, which hopefully will be remedied by its recent release on DVD, but this does not mean that it is without its deficiencies. Particularly, "Undeclared," like The 40 Year-Old-Virgin, showcases a lack of moral assessment when it comes to the sexual conduct of its character. If there is an ethos in Apatow's world -- of which "Freaks and Geeks" can be excluded on the basis that it is ultimately Paul Feig's creation -- it is that people will have sex, period. There is no moral reckoning based on abstract principles.At this point, any viewer of The 40-Year-Old Virgin (or "Undeclared") might challenge this interpretation on the basis that Carell's character final contests that his prolonged virginity has found a meaning in his love for Trish (Catherine Keener, Being John Malkovich), leading them to a very family value-friendly consummation (in terms of its circumstances at least). Even so, up to this point, Carell's sojourn in the land of the untouched proceeded not from a moral calculus of his own but rather out of his particular romantic ineptitude -- he would have if he could have. In other words, Carell's character uses the convenience of his inadequacies to steak out a moral position: his virginity is an accident, meted by his peculiar character flaws. What all of this means is that Apatow has to find a way to redeem Carell, short of simply getting his character laid -- hence the recourse to a love of a lifetime, Firehouse-style.

On the level of conceit, what Apatow has on his hands is a sitcom plot, demanding a twenty-two minute narrative. At 110 minutes, our prolonged wait for Carell's loss of virginity might just resemble his own 40-year frustration. While Apatow deftly pulls off a Hitchcockian shift in audience desire -- we go from wanting to see the poor guy get some to hoping that he will not forsake his love for Trish -- he sure takes his time in getting there. When finally he does, we get one of the most singularly incompetent instances of cross-cutting I can remember in recent cinema -- somebody needs to bone-up on old Griffith. (Oh, and a memo to Judd, there is a difference between racism on-screen in 1915 and in 2005 -- you don't get the same pass that some of us are willing to extend to The Birth of a Nation, provided its very different social circumstances.) When you cut between two plot lines, conceivably to heighten tension and raise the possibility that things won't turn out the way we might like them to, it is best that they somehow intersect. Since it is Beth's (Elizabeth Banks) and not his apartment that they go back to, there is no danger that Trish will walk in on them, thereby deflating any potential for suspense in his use of a technique then generally connotes exactly that; the principle is so elementary, in fact, that one wonders how it is possible for a director with Apatow's experience to screw it up that badly.

Really, though, it is not really Apatow's lack of a moral intelligence and his inadequate filmmaking that makes The 40-Year-Old Virgin frequently unpleasurable viewing. Instead, it is the film's unrelenting profanity and repetitiveness that truly tests the patience of its audience. The scene where Carell's chest hair is removed in one section after another seems to be the perfect metaphor for the viewer who might not automatically embrace Apatow's profane perspective. In the end, The 40-Year-Old Virgin shares its basic structure with another of this summer's most highly-anticipated comedy's, The Aristocrats: the same joke is repeated time and again, with only the slightest of modifications. What does Apatow call his act? The 40-Year-Old Virgin!

There is no similar limitation of scope to Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man, yet another major work from the poet laureate of ecological antagonism and civilizational abandonment. As the director himself puts it in his endlessly fascinating voice-over, nature is not the harmonious entity that the film's subject (and grizzly meal) Timothy Treadwell posits, but is instead characterized by "chaos, disharmony and murder." This is to say that in the story of Treadwell, Herzog has found a subject as comfortable in the director's archetypal universe as were Kaspar Hauser or Fitzcarraldo.

There is no similar limitation of scope to Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man, yet another major work from the poet laureate of ecological antagonism and civilizational abandonment. As the director himself puts it in his endlessly fascinating voice-over, nature is not the harmonious entity that the film's subject (and grizzly meal) Timothy Treadwell posits, but is instead characterized by "chaos, disharmony and murder." This is to say that in the story of Treadwell, Herzog has found a subject as comfortable in the director's archetypal universe as were Kaspar Hauser or Fitzcarraldo. That story, of a man who has left civilization to record and protect Alaskan Brown Bears, only to himself to be devoured by one of the great creatures -- along with his girlfriend -- is presented in a series of home movies made by Treadwell and later assembled and narrated, with additional commentary footage and interviews, by Herzog. More than any other film in recent memory, Grizzly Man thus stands as a case study in the auteur theory: namely that the ultimate measure of a film consists not only in the text but in its extra-textual circumstances and relation to a broader corpus of work as well.

In other words, it gains value by virtue of its status within the director's body of work, which in this case is as a film that presents nature's passive indifference contraposed with a protagonist who thirsts for an escape from a cruel civilization. However it is precisely Treadwell's false, romanticized notions of the ecological other that precipitates his real-life killing: as one bumpkin-ish character notes, Treadwell seemed to treat these beasts as if they were human beings in bear suits rather than the soul-less creatures that Herzog himself memorably analyzes.

Indeed, Grizzly Man is filled with moments of such hermeneutical insight, showing not only the delusions of an individual who had been burnt one too many times by human order, but further of man's subjugation to the cosmos, particularly in this mode of existence. When Treadwell, in spite of his belief system, prays for divine intervention to save the creatures at a moment of ecological crisis, Herzog allows an interpretative space which would seem the only honest conveyance of a causality whose immaterial reality precludes a visual expression. This is to say that Herzog, in his clearly crafted re-presentation of the Treadwell story, does not simply tell, but indeed allows the viewer to contemplate the surfaces that comprise his art. In the end, the stare of the grizzly that Herzog fashions as disinterestedness -- surely the most reasonable explanation, mind you -- retains its inherent ambiguity by virtue of its surface materiality. This is a cinema, in other words, which could not exist in any other medium; this, we might observe, is the very opposite of Apatow's brand of comic filmmaking.

Sunday, August 14, 2005

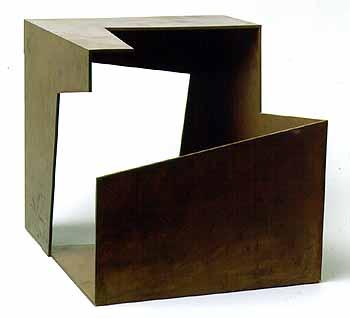

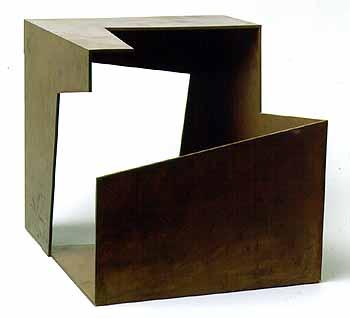

Current Exhibition: Oteiza: Myth and Modernism

The Guggenheim's Oteiza: Myth and Modernism, running now through the 24th, is the first comprehensive survey of the Basque sculptor's work ever to be mounted in this country. That his art not only prefigures 1960s-era minimalism but even exceeds much of it in its theoretical complexity renders any Jorge Oteiza exhibition essential. Yet, because of his limited exposure, Oteiza's reputation isn't what it deserves to be: as one of the key sculptors of the twentieth century.

The corpus of Jorge Oteiza (1908-2003) represents an early expression of the minimalist aesthetic in sculpture, presaging the work of Donald Judd and Basque countryman Eduardo Chillida by more than a decade. Yet it is not simply his timing in art historical terms that lends Oteiza's art its substantial merit, but instead it is the success of his formal experimentation in finding an original idiom through which to express his spiritual content. To be sure, this is an art that seeks to express immaterial, metaphysical reality through the decidedly material means of the sculptural medium. However, it is less matter that dictates the tenor of his work, but rather space which defines Oteiza's aesthetic. Particularly, Oteiza, by the mid 1950s, sought to give life to the negative space that conditioned his craft: in carving slits and "light condensers" into slabs of marble and alabaster, Oteiza called attention to the spatial transformations undergone in the process of sculpture, and moreover, to the fact of an invisible presence in the location of a negative space. Oteiza's work instantiates a world unseen; in absence and through absence, Oteiza depicts presence.

Particularly, Oteiza, by the mid 1950s, sought to give life to the negative space that conditioned his craft: in carving slits and "light condensers" into slabs of marble and alabaster, Oteiza called attention to the spatial transformations undergone in the process of sculpture, and moreover, to the fact of an invisible presence in the location of a negative space. Oteiza's work instantiates a world unseen; in absence and through absence, Oteiza depicts presence.

Naturally, this formal idiom translates religious allegory to the extent that the latter is similarly concerned with the metaphysical. The fact that Oteiza's corpus features such titles as "You are Peter" and "Portrait of the Holy Ghost" confirms this confluence of formal concerns and religious subject matter. Yet, Oteiza's work retains a clear pedagogical dimension apart from its utilization for religious expression. First, there is its function in shaping one's perception of the medium: no longer is sculpture defined by matter, but instead by the space of which that matter is only a part.

Second, as with his alabaster works, the permeability of the sculptural surface is underscored. Then again, this instability of surfaces retains a certain spiritual resonance to the degree that it elicits a fluidity of visible and invisible reality that denies the false posturings of skepticism. To deny immaterial existence is to twine one's epistemology to the very limited sensory experience of seeing. By the limiting means of sculpture, Oteiza conveys a world that far exceeds its material dimension. This is spiritual art of the first order because it asks the necessary formal questions.

Second, as with his alabaster works, the permeability of the sculptural surface is underscored. Then again, this instability of surfaces retains a certain spiritual resonance to the degree that it elicits a fluidity of visible and invisible reality that denies the false posturings of skepticism. To deny immaterial existence is to twine one's epistemology to the very limited sensory experience of seeing. By the limiting means of sculpture, Oteiza conveys a world that far exceeds its material dimension. This is spiritual art of the first order because it asks the necessary formal questions.

The corpus of Jorge Oteiza (1908-2003) represents an early expression of the minimalist aesthetic in sculpture, presaging the work of Donald Judd and Basque countryman Eduardo Chillida by more than a decade. Yet it is not simply his timing in art historical terms that lends Oteiza's art its substantial merit, but instead it is the success of his formal experimentation in finding an original idiom through which to express his spiritual content. To be sure, this is an art that seeks to express immaterial, metaphysical reality through the decidedly material means of the sculptural medium. However, it is less matter that dictates the tenor of his work, but rather space which defines Oteiza's aesthetic.

Particularly, Oteiza, by the mid 1950s, sought to give life to the negative space that conditioned his craft: in carving slits and "light condensers" into slabs of marble and alabaster, Oteiza called attention to the spatial transformations undergone in the process of sculpture, and moreover, to the fact of an invisible presence in the location of a negative space. Oteiza's work instantiates a world unseen; in absence and through absence, Oteiza depicts presence.

Particularly, Oteiza, by the mid 1950s, sought to give life to the negative space that conditioned his craft: in carving slits and "light condensers" into slabs of marble and alabaster, Oteiza called attention to the spatial transformations undergone in the process of sculpture, and moreover, to the fact of an invisible presence in the location of a negative space. Oteiza's work instantiates a world unseen; in absence and through absence, Oteiza depicts presence.Naturally, this formal idiom translates religious allegory to the extent that the latter is similarly concerned with the metaphysical. The fact that Oteiza's corpus features such titles as "You are Peter" and "Portrait of the Holy Ghost" confirms this confluence of formal concerns and religious subject matter. Yet, Oteiza's work retains a clear pedagogical dimension apart from its utilization for religious expression. First, there is its function in shaping one's perception of the medium: no longer is sculpture defined by matter, but instead by the space of which that matter is only a part.

Second, as with his alabaster works, the permeability of the sculptural surface is underscored. Then again, this instability of surfaces retains a certain spiritual resonance to the degree that it elicits a fluidity of visible and invisible reality that denies the false posturings of skepticism. To deny immaterial existence is to twine one's epistemology to the very limited sensory experience of seeing. By the limiting means of sculpture, Oteiza conveys a world that far exceeds its material dimension. This is spiritual art of the first order because it asks the necessary formal questions.

Second, as with his alabaster works, the permeability of the sculptural surface is underscored. Then again, this instability of surfaces retains a certain spiritual resonance to the degree that it elicits a fluidity of visible and invisible reality that denies the false posturings of skepticism. To deny immaterial existence is to twine one's epistemology to the very limited sensory experience of seeing. By the limiting means of sculpture, Oteiza conveys a world that far exceeds its material dimension. This is spiritual art of the first order because it asks the necessary formal questions.

Thursday, August 11, 2005

Dimensions of Dialogue

With the DVD release of Jan Svankmajer's 12-minute animated bricolage Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) earlier this summer, one of the truly singular works of the animated cinema is finally available in the United States. Certainly, Svankmajer's reputation as one of the great Surrealists of his chosen medium was already secure with the wide availability of such recent major works as Conspirators of Pleasure (1996) and Little Otik (2000). However, it is with the relatively diminutive Dimensions of Dialogue that Svankmajer shows himself to be one of the three or four most important artists of the Communist twilight in Eastern Europe. Surely, for the brilliance of its form, the ambitiousness of its subject and the boldness of its critique, Dimensions of Dialogue deserves to be considered in the class of this epoch's greatest achievements and as Svankmajer's masterpiece to wit.

Divided into three separate dialogues entitled 'Exhaustive Discussion,' 'Passionate Discourse' and 'Factual Conversation,' Svankmajer indeed exhausts the subject of social interaction in this unbounded critique of human malfeasance. In the first dialogue, two anthropomorphized assemblages of food-stuffs and kitchen utensils respectively lurch towards one another with the latter devouring the former. In turn, this pattern is repeated when a collection of intellectual markers vies with the kitchen products destroying the returning collage with similarly ease. Next it is the now degraded food objects which sully the books, paints, etc., as though the two were mingling in some fictious trash bin. This process of disintegration continues with the resulting forms appearing closer and closer to the form of man himself.

In the first dialogue, two anthropomorphized assemblages of food-stuffs and kitchen utensils respectively lurch towards one another with the latter devouring the former. In turn, this pattern is repeated when a collection of intellectual markers vies with the kitchen products destroying the returning collage with similarly ease. Next it is the now degraded food objects which sully the books, paints, etc., as though the two were mingling in some fictious trash bin. This process of disintegration continues with the resulting forms appearing closer and closer to the form of man himself.

The resulting clay human figure proceeds to spit out a facsimile of himself, as does the copy and so on. Consequently what this series of degradations finally produces is a human figure to be sure, but one lacking in any distinguishing characteristics. Given this lack of defining humanity, Svankmajer invites his spectator to read the inscribed process in negative terms: in turning over from one identity to the next there is a loss until ultimately, variation from one figure to the next ceases to exist. Moreover, the identities of these figures seem to cast light on the specificity of Svankmajer's critique -- the first seems to figure agrarianism, the second, industrialism, and the third a life of letters perhaps most closely associated with the bourgeoisie. In this series of revolutions, mankind destroys its uniqueness, which provides Svankmajer's 'Exhaustive Discussion' its critical heft; Marx's understanding of class antagonism is the subject of Svankmajer's critique.

Though it hardly seems possible, the second section of Dimensions of Dialogue exceeds even the first in its organic representation of critical discourse within an ostensibly analogical narrative. Here two clay figures, a man and a woman, commence an amorous affair. The two figures literally become indistinguishable from one another as Svankmajer manipulates the forms while utilizing his typical stop-motion technique (as he does in the first and third parts as well). In the midst of their passion, Svankmajer shows great economy depicting their love-making in such visuals as a hand and a breast alone amidst a large, amorphic blob of clay.

Though it hardly seems possible, the second section of Dimensions of Dialogue exceeds even the first in its organic representation of critical discourse within an ostensibly analogical narrative. Here two clay figures, a man and a woman, commence an amorous affair. The two figures literally become indistinguishable from one another as Svankmajer manipulates the forms while utilizing his typical stop-motion technique (as he does in the first and third parts as well). In the midst of their passion, Svankmajer shows great economy depicting their love-making in such visuals as a hand and a breast alone amidst a large, amorphic blob of clay.

Once the pair finish, a small piece of their shared physical intercourse is left bouncing about on the table. Neither wishes to reclaim this lost substance, leading the pair to fling it -- their shared past -- at one another. This emerging antagonism becomes only a prelude as the two, now in full No Exit-mode, proceed to rip each other's faces out. What began as ecstatic passion ends in mutual annihilation; certainly, Svankmajer possesses no less skepticism towards the hope of romantic satisfaction than he does in the benefits of revolution seeded in class conflict.

The final section, 'Factual Conversation,' begins with the harmonious interaction of two male busts as they produce various complementary objects from their mouths. After this first concordant round, they produce objects that no longer work together, producing a relative absurdity and incongruence of interaction which is definitively surreal. Yet, their give-and-take does not stop here. The two continue in this exchange until their respective orifices begin to offer similar, competing objects, which eventually assures their mutual destruction. While it might be tempting to read part three, consequently, as a critique of capitalism -- which it may be -- the more compelling reading, given the film's historical circumstances and the undeniable tenor of the first part, would be as a breakdown of mutual benefit, thereby skewering socialism in equal measure. (Though it might also be tempting to view part three in light of the Cold War provided the above verbal analogy, the shared benefit inscribed would seem to rule out this possibility.)

After this first concordant round, they produce objects that no longer work together, producing a relative absurdity and incongruence of interaction which is definitively surreal. Yet, their give-and-take does not stop here. The two continue in this exchange until their respective orifices begin to offer similar, competing objects, which eventually assures their mutual destruction. While it might be tempting to read part three, consequently, as a critique of capitalism -- which it may be -- the more compelling reading, given the film's historical circumstances and the undeniable tenor of the first part, would be as a breakdown of mutual benefit, thereby skewering socialism in equal measure. (Though it might also be tempting to view part three in light of the Cold War provided the above verbal analogy, the shared benefit inscribed would seem to rule out this possibility.)

Whatever the precise reading is of this third part, however, what does remain clear is that together, Svankmajer underlines the folly of human interaction on the levels of power (political), sex (interpersonal) and capital (financial).

Divided into three separate dialogues entitled 'Exhaustive Discussion,' 'Passionate Discourse' and 'Factual Conversation,' Svankmajer indeed exhausts the subject of social interaction in this unbounded critique of human malfeasance.

In the first dialogue, two anthropomorphized assemblages of food-stuffs and kitchen utensils respectively lurch towards one another with the latter devouring the former. In turn, this pattern is repeated when a collection of intellectual markers vies with the kitchen products destroying the returning collage with similarly ease. Next it is the now degraded food objects which sully the books, paints, etc., as though the two were mingling in some fictious trash bin. This process of disintegration continues with the resulting forms appearing closer and closer to the form of man himself.

In the first dialogue, two anthropomorphized assemblages of food-stuffs and kitchen utensils respectively lurch towards one another with the latter devouring the former. In turn, this pattern is repeated when a collection of intellectual markers vies with the kitchen products destroying the returning collage with similarly ease. Next it is the now degraded food objects which sully the books, paints, etc., as though the two were mingling in some fictious trash bin. This process of disintegration continues with the resulting forms appearing closer and closer to the form of man himself. The resulting clay human figure proceeds to spit out a facsimile of himself, as does the copy and so on. Consequently what this series of degradations finally produces is a human figure to be sure, but one lacking in any distinguishing characteristics. Given this lack of defining humanity, Svankmajer invites his spectator to read the inscribed process in negative terms: in turning over from one identity to the next there is a loss until ultimately, variation from one figure to the next ceases to exist. Moreover, the identities of these figures seem to cast light on the specificity of Svankmajer's critique -- the first seems to figure agrarianism, the second, industrialism, and the third a life of letters perhaps most closely associated with the bourgeoisie. In this series of revolutions, mankind destroys its uniqueness, which provides Svankmajer's 'Exhaustive Discussion' its critical heft; Marx's understanding of class antagonism is the subject of Svankmajer's critique.

Though it hardly seems possible, the second section of Dimensions of Dialogue exceeds even the first in its organic representation of critical discourse within an ostensibly analogical narrative. Here two clay figures, a man and a woman, commence an amorous affair. The two figures literally become indistinguishable from one another as Svankmajer manipulates the forms while utilizing his typical stop-motion technique (as he does in the first and third parts as well). In the midst of their passion, Svankmajer shows great economy depicting their love-making in such visuals as a hand and a breast alone amidst a large, amorphic blob of clay.

Though it hardly seems possible, the second section of Dimensions of Dialogue exceeds even the first in its organic representation of critical discourse within an ostensibly analogical narrative. Here two clay figures, a man and a woman, commence an amorous affair. The two figures literally become indistinguishable from one another as Svankmajer manipulates the forms while utilizing his typical stop-motion technique (as he does in the first and third parts as well). In the midst of their passion, Svankmajer shows great economy depicting their love-making in such visuals as a hand and a breast alone amidst a large, amorphic blob of clay. Once the pair finish, a small piece of their shared physical intercourse is left bouncing about on the table. Neither wishes to reclaim this lost substance, leading the pair to fling it -- their shared past -- at one another. This emerging antagonism becomes only a prelude as the two, now in full No Exit-mode, proceed to rip each other's faces out. What began as ecstatic passion ends in mutual annihilation; certainly, Svankmajer possesses no less skepticism towards the hope of romantic satisfaction than he does in the benefits of revolution seeded in class conflict.

The final section, 'Factual Conversation,' begins with the harmonious interaction of two male busts as they produce various complementary objects from their mouths.

After this first concordant round, they produce objects that no longer work together, producing a relative absurdity and incongruence of interaction which is definitively surreal. Yet, their give-and-take does not stop here. The two continue in this exchange until their respective orifices begin to offer similar, competing objects, which eventually assures their mutual destruction. While it might be tempting to read part three, consequently, as a critique of capitalism -- which it may be -- the more compelling reading, given the film's historical circumstances and the undeniable tenor of the first part, would be as a breakdown of mutual benefit, thereby skewering socialism in equal measure. (Though it might also be tempting to view part three in light of the Cold War provided the above verbal analogy, the shared benefit inscribed would seem to rule out this possibility.)

After this first concordant round, they produce objects that no longer work together, producing a relative absurdity and incongruence of interaction which is definitively surreal. Yet, their give-and-take does not stop here. The two continue in this exchange until their respective orifices begin to offer similar, competing objects, which eventually assures their mutual destruction. While it might be tempting to read part three, consequently, as a critique of capitalism -- which it may be -- the more compelling reading, given the film's historical circumstances and the undeniable tenor of the first part, would be as a breakdown of mutual benefit, thereby skewering socialism in equal measure. (Though it might also be tempting to view part three in light of the Cold War provided the above verbal analogy, the shared benefit inscribed would seem to rule out this possibility.) Whatever the precise reading is of this third part, however, what does remain clear is that together, Svankmajer underlines the folly of human interaction on the levels of power (political), sex (interpersonal) and capital (financial).

Saturday, August 06, 2005

New Film: Broken Flowers and 2046

How much of Broken Flowers can be attributed to director Jim Jarmusch's contribution and how much to Bill Murray's? Though the auteur theory seems to have been made for corpuses like Jarmusch's -- as uniform as it is in style and point-of-view -- there can be no mistaking the consistency of Murray's performance in Broken Flowers with his recent work for directors as disparate as Jarmusch (also Coffee and Cigarettes, 2003), Sofia Coppola (Lost in Translation, 2003) and Wes Anderson (Rushmore, 1998; The Royal Tenenbaums, 2001; and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, 2004). Increasingly, Mr. Murray looks as if he is little more than a Cossack away from starring in a series of lost Bresson features. Then again, performance style itself is meaningless without the manner in which the actors are framed and the quality of light that illuminates their gestures. Bill Murray may set a new standard for dead-pan in Broken Flowers, but without the over-arching structure and articulating style of the film, his performative restraint is meaningless.

How much of Broken Flowers can be attributed to director Jim Jarmusch's contribution and how much to Bill Murray's? Though the auteur theory seems to have been made for corpuses like Jarmusch's -- as uniform as it is in style and point-of-view -- there can be no mistaking the consistency of Murray's performance in Broken Flowers with his recent work for directors as disparate as Jarmusch (also Coffee and Cigarettes, 2003), Sofia Coppola (Lost in Translation, 2003) and Wes Anderson (Rushmore, 1998; The Royal Tenenbaums, 2001; and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, 2004). Increasingly, Mr. Murray looks as if he is little more than a Cossack away from starring in a series of lost Bresson features. Then again, performance style itself is meaningless without the manner in which the actors are framed and the quality of light that illuminates their gestures. Bill Murray may set a new standard for dead-pan in Broken Flowers, but without the over-arching structure and articulating style of the film, his performative restraint is meaningless.So it is back to Jarmusch's contribution, which in terms of the work's style is unmistakable: typically, Broken Flowers features the director's use of fades to mark scene-changes, an often static camera, his frequent recourse to pillow shots -- especially in the film's numerous traveling sequences -- which once again mark the director as Ozu's clearest follower in the American cinema -- and even a Bressonian restraint which Murray brings flawlessly to screen. Collectively, these elements of style bring to life the story of Don Johnston -- not to be mistaken with, wait.. give me a second to catch my breath... Don Johnson -- an over-the-hill Don Juan (as we are told two hundred and forty-six times in the first ten minutes of the film) who discovers that he might have long-lost son from one of his many affairs. With Murray's Johnston being persistently brow-beaten by would-be private eye neighbor Jeffrey Wright, the former sets off in search of the mother of his potential off-spring, thereby mixing elements of detective fiction and the road movie, a favorite genre of the Stranger Than Paradise-auteur.

In terms of the women whom he visits -- played by Sharon Stone, Frances Conroy, Jessica Lange, and Tilda Swinton respectively -- Jarmusch tends towards schematics, producing something of a coiling miasma of Middle American banality: its not just that Jarmusch gets much of his financing from Europe, but no small portion of his perspective as well. Yet aside from this bit of slouching towards the Brothers Coen and a few flat jokes (including Sharon Stone's seductress daughter being named Lolita), the Director's typically-dry sense of humor remains in tact, which surely is a good thing given the work's dark denouement. In the end, Broken Flowers does offer a modicum of resolution even as it maintains the openness that has long signified the director's craft. Indeed, there is a fundamental relativity to his art which is best stated by Murray himself near the end of the film: "the past is gone... the future isn't here yet... so all there is is this, the present."

However, there does exist a fundamental flaw to Jarmusch's basic conceit: the present itself is the most unstable category of all, forever dying the moment it comes into existence. Wong Kar-wai's 2046 operates with this understanding, belying the impossibility of Jarmusch's philosophical gloss -- the present is never immune from the past, nor can the future escape an ever-constricting set of possibilities conditioned by what has already come into being. When Chow awakens to his feelings for Fei Wong's (Chungking Express, 1994) Wang, it becomes clear that they will never get together, not because she isn't interested, but rather for the fact that she is already in love. As the voice over narration states, "love is matter of timing; it is no use meeting the right person too early or too late."

However, there does exist a fundamental flaw to Jarmusch's basic conceit: the present itself is the most unstable category of all, forever dying the moment it comes into existence. Wong Kar-wai's 2046 operates with this understanding, belying the impossibility of Jarmusch's philosophical gloss -- the present is never immune from the past, nor can the future escape an ever-constricting set of possibilities conditioned by what has already come into being. When Chow awakens to his feelings for Fei Wong's (Chungking Express, 1994) Wang, it becomes clear that they will never get together, not because she isn't interested, but rather for the fact that she is already in love. As the voice over narration states, "love is matter of timing; it is no use meeting the right person too early or too late."Of course, Wang is not Chow's first love interest in 2046. She follows a series of one night-stands, her own incursion as a non-romantic presence, and Chow's fling with the incomparable Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi, House of Flying Daggers). In Wong's universe, nothing lasts -- people come into our lives, move out of them, and in some cases reappear, as with Faye Wong's character. In Chow and Wang's case, it is not a matter of lovers reuniting, but rather casual acquaintances who become much closer during a second go-round. In this second turn, she begins to assist Chow in his writing. He in turn pens "2047," named after the room in which he lives, and in which they now work. While this text is ostensibly concerned with her absent Japanese lover, the narrator admits that Chow is the true subject of this oblique take on his own feelings for Wang. Importantly, this same Japanese lover is the protagonist in a second novel, "2046," thereby establishing that the film of the same name is also about its author: Wong.

At the end of the film's prequel In the Mood for Love (2000), Leung's character whispers a secret into a wall. 2046 overtly instantiates the substance of his feelings -- or rather Wong's -- not only at the moment of confession but over the course of the director's entire career, even if he sustains the same degree of mystery that "2047" purportedly does: to everyone but (perhaps) those involved. In this way, 2046 is not only the most self-reflexive work of the director's career, but is in fact the fulfillment of a trilogy begun with Days of Being Wild (1991) and continued in In the Mood for Love. Wong shares the secrets of his deepest feelings -- and those of his art -- though with the same degree of abstraction as his fictional science fiction novel "2046." Significantly, this choice of genre is an organically-chosen means for referring to the same obliqueness with which Wong narrates his own feelings.

Lest all of this makes 2046 seem overly-intellectual, the reality is that Wong remains the most purely visceral filmmaker alive today. If Abbas Kiarostami's films pose the great formal questions of our time, Wong makes us feel as no other director can. He is the great aesthete of his time, attuned to the curve of a woman's hip and how the slit in her skirt rides up the side of her leg as no one else is. Then again, his films offer a form that is both original and that breathlessly express his own anxieties: just as people move in and out of other's lives, so do the narratives of his seemingly aleatory art emerge and collapse. 2046 becomes all the more essential for its role in the clarifying this very process.

Friday, August 05, 2005

Recommended Propaganda: Went the Day Well?

Alberto Cavalcanti's Went the Day Well? (1942) is the sort of film that gives me pause concerning one of my firmer held beliefs: that the measure of a film's value lies not in what is said, but in how it says it. You see, Cavalcanti's picture is a piece of British war propaganda, made in 1942, which paints the British public as a noble fraternity -- duplicitous double agents aside -- sacrificing everything in order to defeat the common enemy. It is not just the men of Bramley Green who put their lives on the line to defeat their German captors, but the women and even the children who do so as well.  Went the Day Well? does not shy away from the collateral costs of war nor does it merely schematize the Germans as a bumbling, easy to defeat opponent. This is a work of the highest level of integrity that no less than expected its spectators to show the same vigilance as those who gave their lives to defeat the enemy force. Cavalcanti's picture is a work of profound nobility.

Went the Day Well? does not shy away from the collateral costs of war nor does it merely schematize the Germans as a bumbling, easy to defeat opponent. This is a work of the highest level of integrity that no less than expected its spectators to show the same vigilance as those who gave their lives to defeat the enemy force. Cavalcanti's picture is a work of profound nobility.

Of course, some of what I have just mentioned is not strictly a matter of content, but is likewise attributable to the film's particular form. For instance, Cavalcanti's representation of the Germans as a competent military force -- not always the rule in the period's films -- proves essential in the film's discourse, and ultimately its strength as propaganda: they cannot be easily beaten; it will take extreme fortitude. On a visceral level, moreover, Went the Day Well? also benefits from Cavalcanti's dexterous manipulation of suspense. (This quality is also evident in his subsequent They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), perhaps the greatest British postwar thriller -- exceeding even Carol Reed's better-remembered classic, The Third Man [1949]). With Went the Day Well, one of the key components of his mastery of tension is his use of sound. In one of the key scenes, where the British civilians have escaped their German captors, Cavalcanti completely cuts the sound altogether, thereby translating this affected silence into the veil of night that the medium's visual mandate precludes. No film, after all, can represent action in complete darkness. So, in this way the distinction established at the outset -- between the telling and the message -- is moot. Went the Day Well? excels in both its form and its moral resoluteness.

Went the Day Well? does not shy away from the collateral costs of war nor does it merely schematize the Germans as a bumbling, easy to defeat opponent. This is a work of the highest level of integrity that no less than expected its spectators to show the same vigilance as those who gave their lives to defeat the enemy force. Cavalcanti's picture is a work of profound nobility.

Went the Day Well? does not shy away from the collateral costs of war nor does it merely schematize the Germans as a bumbling, easy to defeat opponent. This is a work of the highest level of integrity that no less than expected its spectators to show the same vigilance as those who gave their lives to defeat the enemy force. Cavalcanti's picture is a work of profound nobility.Of course, some of what I have just mentioned is not strictly a matter of content, but is likewise attributable to the film's particular form. For instance, Cavalcanti's representation of the Germans as a competent military force -- not always the rule in the period's films -- proves essential in the film's discourse, and ultimately its strength as propaganda: they cannot be easily beaten; it will take extreme fortitude. On a visceral level, moreover, Went the Day Well? also benefits from Cavalcanti's dexterous manipulation of suspense. (This quality is also evident in his subsequent They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), perhaps the greatest British postwar thriller -- exceeding even Carol Reed's better-remembered classic, The Third Man [1949]). With Went the Day Well, one of the key components of his mastery of tension is his use of sound. In one of the key scenes, where the British civilians have escaped their German captors, Cavalcanti completely cuts the sound altogether, thereby translating this affected silence into the veil of night that the medium's visual mandate precludes. No film, after all, can represent action in complete darkness. So, in this way the distinction established at the outset -- between the telling and the message -- is moot. Went the Day Well? excels in both its form and its moral resoluteness.

Wednesday, August 03, 2005

Looking at Ford, Looking through Hawks

"I repeat myself in keeping with Orson Welles who after viewing Stagecoach 40 times before embarking on Citizen Kane said he was influenced by the old guys; the 'classical' film makers, by which he meant 'John Ford, John Ford and John Ford.' If the pantheon of classical music is 'the three Bs' (Bach, Beethoven and Brahms), then it is arguable there is only one true great in cinema - and that's the man who won more Academy Awards (five) than anyone before or since."

-Richard Franklin

"The problem lies in Hawks's apparent transparency, in a stylistic presence that is relentlessly invisible, self-effacing, difficult to see, and extremely difficult to analyze. The subtlety of Hawks's style is one of the most significant features of his work, but it is also the greatest obstacle to the widespread recognition of his talent as a film-maker."

-John Belton

Atop the pantheon of great Hollywood directors, three men tower above the rest -- and with all due deference to Richard Franklin, these men are not named John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. Well, one of them is, but the other two preferred to go by their given names, Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. In the case of the former, no further allowances need be made at the present: few filmmaker's can claim an academic journal devoted entirely to the scholarly research of their career's as can the 'Master of Suspense' (for the record, the publication in question is the Hitchcock Annual, edited by a former professor of mine, Richard Allen). Hawks, on the other hand, remains the red-headed step child of the big three, never quite reaching the same level of international acclaim as the other two; his corpus seems to lack a Vertigo (1958) or a Searchers (1956), which is to say a single masterpiece generally considered to be not only his best, but further one of the great works of world cinema.

Again, much of the difficultly surrounding Hawks's work lies not so much in his choice of subjects or in his themes, but instead in the apparent invisibility of his style. Ford is the perfect counterpoint to the Hawks's visual schema. To paint the great director of western's in the broadest of brushstrokes, Ford's is a cinema devoted to a mythology of the West, whereby the wilderness is painstakingly brought under the thumb of civilization. This cursory explanation for his primary mega-theme is consequently translated into imagery that contraposes a nascent civilization and said wilds. Take for instance the adjacent image from My Darling Clementine (1946): here, Henry Fonda's Wyatt Earp reclines on a porch overlooking the wilderness that surrounds the ominously-named Tombstone. In so doing, Ford has visualized his principle theme, inasmuch as Earp (and Tombstone) itself) stands for an ordering force challenging a brutal nature. A second exact visual expression of Ford's ideas occurs in the sequence where a dance is staged at the site of the church's construction. With the half-built structure allowing a vantage out onto the surrounding desert, Ford effectively imparts his basic conflict visually: the wilderness is being tamed with the aid of society's bedrock institutions, the church and the law. Our understanding of his art is therefore deepened by our reading of his imagery. In the interplay of the foreground and background, Ford establishes his principle dialectic.

Take for instance the adjacent image from My Darling Clementine (1946): here, Henry Fonda's Wyatt Earp reclines on a porch overlooking the wilderness that surrounds the ominously-named Tombstone. In so doing, Ford has visualized his principle theme, inasmuch as Earp (and Tombstone) itself) stands for an ordering force challenging a brutal nature. A second exact visual expression of Ford's ideas occurs in the sequence where a dance is staged at the site of the church's construction. With the half-built structure allowing a vantage out onto the surrounding desert, Ford effectively imparts his basic conflict visually: the wilderness is being tamed with the aid of society's bedrock institutions, the church and the law. Our understanding of his art is therefore deepened by our reading of his imagery. In the interplay of the foreground and background, Ford establishes his principle dialectic.

The opposite is true of the cinema of Howard Hawks: if we look at the screen in Ford, we look through it in Hawks. First, while Ford is primarily concerned with the mythology of the West, Hawks seems to have no similar predilection for this subject matter. Rather what is most remarkable about the latter's corpus, famously dispersed over a wide variety genres -- including the western -- is its uniform interest in homo-social groups of men (and occasionally the spare woman) who are continually shown at work. As Andrew Sarris once put it so succinctly, the basic thread running through his cinema is that "man is measured by his work... not in his ability to communicate with women." This concern, again, manifests across genre boundaries, becoming the key theme in his own great western, Rio Bravo (1959), where Dude (Dean Martin) struggles with his own alcoholism, finally finding redemption in his renewed professional ability.

Similarly, John Wayne's John T. Chance, in an explicit reversal of Fred Zinnemann's High Noon (1952) matrix, must depend upon the help of others, even as he attempts to go it alone. This dialectic between an individualist ethos and his dependence upon the group is no less profoundly American in its analysis... but I digress; the point is that Ford's themes are central to the genre of which he is the most famous practitioner, while Hawks's manifest themselves time and again, across a wide array of genres.

But what does this have to do with the visual substance of Hawks's work? For the director, form is subservient to the greater themes of the work -- no less than Ford, in fact, form and discourse are consubstantial. Their intermingling, however, is expressed in a very different fashion: whereas, once more, Ford communicates the garden-wilderness dichotomy visually, among other ways, Hawks explicates his themes with a style that expresses his ideas cleanly and without distraction. He shoots his human subjects straight-on (just below eye-level) in comparison with Ford's favored lower angles, looking up at his heroic subject matter. Hawks's figures are commonly staged within the same space -- in two's, etc. -- at a medium distance. When his group is larger than two or three persons, his staging tends to recede to a middle distance that allows his character's to interact in a unified space. Very little action occurs in the background, which varies in size depending upon his utilization of the middle ground, which again flows from the number of characters who populate the scene. In any case, the interactions occur quite near to the camera.

A perfect illustration of Hawks's style can be found in the brilliant opening scene of His Girl Friday (1940). Here, Hawks cuts only when the content precipitates a change in framing or when it is merited, in order to accentuate an important moment in the drama. An example of the latter would be Hawks's cut when Hildy reacts to Walter's off-handed proposal of (re)marriage.

(1940). Here, Hawks cuts only when the content precipitates a change in framing or when it is merited, in order to accentuate an important moment in the drama. An example of the latter would be Hawks's cut when Hildy reacts to Walter's off-handed proposal of (re)marriage.

In so rigorously maintaining this schema, Hawks effects an invisibility to the degree the camera, in following the action with a very plain compositional style, refuses to call attention to itself. Thematically, his perpendicular camera, staging of characters so that they are able to interact within a single space, and unobtrusive editing all instantiate formal corollaries to the director's egalitarian vision. The problem is, with regard to his work's formal comprehension, that each of these techniques makes his artistry disappear. Then again, his egalitarian world view demands nothing less than his unpretentious mise-en-scene.

Ultimately, we look past the visual art of Hawks, through to a broader set of themes and concerns that appear and reappear in work after work. The form of his cinema is independent of the content in terms of its relation to genre; then again, Hawks's camera work and editing precisely enacts the ideology contained in his art. The point is that his world view necessitates an essential artlessness, and is protean mastery of genre demands light stylistic footprints, provided that his work is to maintain a thematic unity.

Returning thus to the above comparison, whereas Ford uses the space of his art to juxtapose conflict, Hawks's space is the location of his enacted subject matter. That his individual shots are so profoundly unmemorable, therefore, becomes part of this matrix. Again, we see through Hawks's films, figuratively, to the content, while in Ford's graphic constructions we see his ideology. In this basic difference, we see the very substance of their art.

-Richard Franklin

"The problem lies in Hawks's apparent transparency, in a stylistic presence that is relentlessly invisible, self-effacing, difficult to see, and extremely difficult to analyze. The subtlety of Hawks's style is one of the most significant features of his work, but it is also the greatest obstacle to the widespread recognition of his talent as a film-maker."

-John Belton

Atop the pantheon of great Hollywood directors, three men tower above the rest -- and with all due deference to Richard Franklin, these men are not named John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. Well, one of them is, but the other two preferred to go by their given names, Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. In the case of the former, no further allowances need be made at the present: few filmmaker's can claim an academic journal devoted entirely to the scholarly research of their career's as can the 'Master of Suspense' (for the record, the publication in question is the Hitchcock Annual, edited by a former professor of mine, Richard Allen). Hawks, on the other hand, remains the red-headed step child of the big three, never quite reaching the same level of international acclaim as the other two; his corpus seems to lack a Vertigo (1958) or a Searchers (1956), which is to say a single masterpiece generally considered to be not only his best, but further one of the great works of world cinema.

Again, much of the difficultly surrounding Hawks's work lies not so much in his choice of subjects or in his themes, but instead in the apparent invisibility of his style. Ford is the perfect counterpoint to the Hawks's visual schema. To paint the great director of western's in the broadest of brushstrokes, Ford's is a cinema devoted to a mythology of the West, whereby the wilderness is painstakingly brought under the thumb of civilization. This cursory explanation for his primary mega-theme is consequently translated into imagery that contraposes a nascent civilization and said wilds.

Take for instance the adjacent image from My Darling Clementine (1946): here, Henry Fonda's Wyatt Earp reclines on a porch overlooking the wilderness that surrounds the ominously-named Tombstone. In so doing, Ford has visualized his principle theme, inasmuch as Earp (and Tombstone) itself) stands for an ordering force challenging a brutal nature. A second exact visual expression of Ford's ideas occurs in the sequence where a dance is staged at the site of the church's construction. With the half-built structure allowing a vantage out onto the surrounding desert, Ford effectively imparts his basic conflict visually: the wilderness is being tamed with the aid of society's bedrock institutions, the church and the law. Our understanding of his art is therefore deepened by our reading of his imagery. In the interplay of the foreground and background, Ford establishes his principle dialectic.

Take for instance the adjacent image from My Darling Clementine (1946): here, Henry Fonda's Wyatt Earp reclines on a porch overlooking the wilderness that surrounds the ominously-named Tombstone. In so doing, Ford has visualized his principle theme, inasmuch as Earp (and Tombstone) itself) stands for an ordering force challenging a brutal nature. A second exact visual expression of Ford's ideas occurs in the sequence where a dance is staged at the site of the church's construction. With the half-built structure allowing a vantage out onto the surrounding desert, Ford effectively imparts his basic conflict visually: the wilderness is being tamed with the aid of society's bedrock institutions, the church and the law. Our understanding of his art is therefore deepened by our reading of his imagery. In the interplay of the foreground and background, Ford establishes his principle dialectic.The opposite is true of the cinema of Howard Hawks: if we look at the screen in Ford, we look through it in Hawks. First, while Ford is primarily concerned with the mythology of the West, Hawks seems to have no similar predilection for this subject matter. Rather what is most remarkable about the latter's corpus, famously dispersed over a wide variety genres -- including the western -- is its uniform interest in homo-social groups of men (and occasionally the spare woman) who are continually shown at work. As Andrew Sarris once put it so succinctly, the basic thread running through his cinema is that "man is measured by his work... not in his ability to communicate with women." This concern, again, manifests across genre boundaries, becoming the key theme in his own great western, Rio Bravo (1959), where Dude (Dean Martin) struggles with his own alcoholism, finally finding redemption in his renewed professional ability.

Similarly, John Wayne's John T. Chance, in an explicit reversal of Fred Zinnemann's High Noon (1952) matrix, must depend upon the help of others, even as he attempts to go it alone. This dialectic between an individualist ethos and his dependence upon the group is no less profoundly American in its analysis... but I digress; the point is that Ford's themes are central to the genre of which he is the most famous practitioner, while Hawks's manifest themselves time and again, across a wide array of genres.

But what does this have to do with the visual substance of Hawks's work? For the director, form is subservient to the greater themes of the work -- no less than Ford, in fact, form and discourse are consubstantial. Their intermingling, however, is expressed in a very different fashion: whereas, once more, Ford communicates the garden-wilderness dichotomy visually, among other ways, Hawks explicates his themes with a style that expresses his ideas cleanly and without distraction. He shoots his human subjects straight-on (just below eye-level) in comparison with Ford's favored lower angles, looking up at his heroic subject matter. Hawks's figures are commonly staged within the same space -- in two's, etc. -- at a medium distance. When his group is larger than two or three persons, his staging tends to recede to a middle distance that allows his character's to interact in a unified space. Very little action occurs in the background, which varies in size depending upon his utilization of the middle ground, which again flows from the number of characters who populate the scene. In any case, the interactions occur quite near to the camera.

A perfect illustration of Hawks's style can be found in the brilliant opening scene of His Girl Friday

(1940). Here, Hawks cuts only when the content precipitates a change in framing or when it is merited, in order to accentuate an important moment in the drama. An example of the latter would be Hawks's cut when Hildy reacts to Walter's off-handed proposal of (re)marriage.

(1940). Here, Hawks cuts only when the content precipitates a change in framing or when it is merited, in order to accentuate an important moment in the drama. An example of the latter would be Hawks's cut when Hildy reacts to Walter's off-handed proposal of (re)marriage. In so rigorously maintaining this schema, Hawks effects an invisibility to the degree the camera, in following the action with a very plain compositional style, refuses to call attention to itself. Thematically, his perpendicular camera, staging of characters so that they are able to interact within a single space, and unobtrusive editing all instantiate formal corollaries to the director's egalitarian vision. The problem is, with regard to his work's formal comprehension, that each of these techniques makes his artistry disappear. Then again, his egalitarian world view demands nothing less than his unpretentious mise-en-scene.

Ultimately, we look past the visual art of Hawks, through to a broader set of themes and concerns that appear and reappear in work after work. The form of his cinema is independent of the content in terms of its relation to genre; then again, Hawks's camera work and editing precisely enacts the ideology contained in his art. The point is that his world view necessitates an essential artlessness, and is protean mastery of genre demands light stylistic footprints, provided that his work is to maintain a thematic unity.

Returning thus to the above comparison, whereas Ford uses the space of his art to juxtapose conflict, Hawks's space is the location of his enacted subject matter. That his individual shots are so profoundly unmemorable, therefore, becomes part of this matrix. Again, we see through Hawks's films, figuratively, to the content, while in Ford's graphic constructions we see his ideology. In this basic difference, we see the very substance of their art.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)