The fact that Russian Ark is comprised of a single, 90-plus minute take might give one the wrong impression: that the picture is primarily a technical tour-de-force. Of course, the details of its production only add to this misconception. To begin with, Russian Ark was filmed entirely within the Hermitage of St. Petersburg, which because of its international cultural status required that director Aleksandr Sokurov and his crew complete the shoot in a single day (on the 23rd of December, 2001). After four years of development, filming commenced with over 1,000 actors, three orchestras and countless technicians. Sokurov entrusted the operation of a lone high-definition video camera to steadycam operator Tilman Büttner (Run Lola Run, 1998), whose task was to realize the director’s vision of three hundred years of Russian history in a single mobile take. Following three false starts, each of which were aborted around the ten minute mark, Russian Ark wrapped after a successful fourth attempt, thereby making history as the world’s first one-take feature, and achieving the director’s purpose of making a film “in one breath.”

Aleksandr Sokurov was born during the summer of 1951 in the former Soviet village of Podorvikha (located within the Irkutsk district).[i] As a young adult, Sokurov enrolled in Gorky University where he later earned a degree in history. In 1975, Sokurov switched courses, entering the Producer's Department at the All-Union Cinematography Institute (VGIK, Moscow). There, he soon came into conflict with the school’s administration, forcing the future director to finish a year early after his student works in cinematography were condemned for their formalism and their “anti-Soviet views.” (In hindsight, both accusations were undoubtedly accurate.) Nevertheless, the director’s first feature, The Lonely Voice of Man (1978-87), which was not accepted for graduation, received numerous prizes and the support of legendary Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, who helped Sokurov find work at the Lenfilm studio in 1980. To be sure, Tarkovsky has remained Sokurov’s primary influence ever since, providing the latter with a template for poetic and one might say spiritual filmmaking. These qualities are apparent in a series of masterworks that include Days of Eclipse (1988), The Second Circle (1990) and Sokurov’s signature Mother and Son (1997), all of which have won numerous international prizes for the Russian auteur.

In fact, Tarkovsky’s impact extends even to Russian Ark, where Sokurov’s aesthetic echoes the older director’s increasing use of longer takes late in his career (many of which run to six minutes or longer, including The Sacrifice’s [1986] extraordinary penultimate sequence-shot). However, it is outside of a Russian context that one sees the clearest precursors for Sokurov’s one-take strategy. Both Miklós Jancsó’s The Red and the White (1967, Hungary) and Theo Angelopoulos’ The Traveling Players (1975, Greece), for example, mobilize long takes and crowd movements to effect temporal passage within the boundaries of a single shot. Similarly in Japan, Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 masterpiece Ugetsu inaugurated the technique of introducing subjective variation within the space and time of a camera movement, via the director’s presentation of an encounter between the film’s male protagonist and his late wife. Nevertheless, while each of these antecedents attained an unprecedented level complexity in terms of their staging, the limits imposed by Sokurov’s subject created a number of unique impediments, any of which could have ended the production of Russian Ark permanently: a light burning out at an inopportune time, an actor flubbing his or her lines, or the camera lens steaming up as action moved from the courtyard back into the museum. Anticipating the last of these, Sokurov conducted experiments in a freezer and lacking the conclusive evidence he needed, lit a candle in a church, where he prayed for the success of his shoot.[ii]

Viewing Russian Ark in light of the challenges posed by the production, a certain tension – or even drama – is created by the film’s unspooling. Then again, to scrutinize Russian Ark in these terms would be to miss the point of Sokurov’s adoption of a one-take format (and to deviate from the way in which most spectators attend to the film). Indeed, one of the more remarkable qualities of Russian Ark is the ease with which the viewer forgets that they are watching a single-take picture. By the time the film concludes, it is less the technical bravura that is in evidence, than the melancholic mood that permeates the nobility’s final exit from the Winter Palace. An overwhelming emotional heft accompanies the film’s denouement, confirming Russian Ark’s elegiac status, which in its case pertains to the passing of high Russian and European civilization. As the ever-present off-screen narrator (voiced by Sokurov himself) says to his on-screen companion, Sergei Dreiden as the historical Marquis de Custine, “Farewell, Europe.” Thus, Russian Ark eulogizes not only the pre-Revolution Russian history that is instantiated by Sokurov’s cast of thousands which fill the grand hallways and ballrooms of the Hermitage, but also the beauty and majesty of this waning civilization: it is for the Canova at which the Stranger shouts “Mama” and for Rembrandt’s late masterwork "The Prodigal Son" upon which Sokurov and Büttner’s camera lingers and for Catherine the Great’s priceless china that is used during the dinner service; and it is for the costuming produced by the crew’s sixty-five designers, the music performed by Russian Ark’s three orchestras, and for the ephemeral qualities of the ball sequence depicted at the picture’s end – that is, for the dances, the gesturing, etc.

Therefore, it becomes clear that Russian Ark’s title is descriptive of its purpose: namely, to preserve a culture that continues to disappear. Sokurov’s use of the term ‘ark’ to describe this process is far from accidental: as the shot’s digitally-enhanced conclusion makes clear, the museum itself (or perhaps more accurately, the film) is this ark and is “destined to sail forever.” (Sokurov even adds rolling waves to the landlocked wintry exterior.) In this way, Russian Ark demonstrates both its currency among contemporary European cinema and also its integral position to the director’s oeuvre. With respect to the former, Russian Ark’s focus on a crumbling civilization situates the film in a fin-de-siècle tradition that also includes Michael Haneke’s The Seventh Continent (1989), Manoel de Oliveira’s Abraham’s Valley (1993), Raoul Ruiz’s Time Regained (1999; Ruiz likewise utilizes the technique of combining tracking shots with zooms to reshape spatial dimensions in his own narrative of time travel). As far as the director’s own corpus is concerned, contrary to the opinion of many critics, Russian Ark is very much of a piece with many of the director’s previous works: Russian Ark seems to complete a cycle of films – most of which feature the word ‘elegy’ in their titles – that similarly eulogize. Indeed, as with the director’s previous Elegy of a Voyage (2001), Russian Ark tours a museum’s galleries, though unlike that former film or indeed any of the other works that likewise comprise said cycle, Russian Ark greatly exceeds Sokurov’s previous efforts in terms of the scope of its production. As such, Russian Ark might just be the endpoint of the director’s aesthetic, and perhaps even its culmination.[iii]

At the same time, Russian Ark’s form remains a function of its content, not simply the latest manifestation of a personal style. Again, Russian Ark depicts three hundred years of the nation’s history – that is, of the transformation in the Hermitage’s use – beginning with Peter the Great (the city’s founder) and ending in the present among the gallery goers, though the narrative follows no similar trajectory. Throughout, the Marquis and the off-camera narrator snake through various historical moments, at times interacting with the palace’s population, and in other instances remaining invisible to the instruments of history. Through their tour a unitary fractal of time and space – a single shot – is maintained, even as the mise-en-scène cedes from one historical moment to the next. In fact, it is Sokurov’s careful delineation of on- and off-camera space that allows so many disparate times to coexist within the museum walls. Not only are new moments in the museum’s history broached when our guides cross through the palace’s thresholds from one room to the next, but indeed the space outside the frame is constantly remaking itself according to its next historical stage, just as Sokurov transforms the disclosed museum that exists before our eyes. Sokurov and Büttner transform on-camera space by pairing their forward tracking camera with zooms that effectively flatten or stretch the space in view, thereby producing a visual analogy for the historical transformations that shape the narrative. At the same time, Sokurov’s insistent use of a single take reaffirms the spatial unity of the museum. That is, if the contents of the space are being transformed over the course of Sokurov’s narrative, its basic scaffolding remains secure. Sokurov’s ‘ark’ therefore is a vessel of time – or multiple times – preserving again far more than the material objects on view in the Hermitage. Russian Ark enshrines the past, utilizing the specificity of an unbroken sequence of moving images to unite the broad scope of the palace’s history. Thus, Russian Ark creates a new form of montage that depends not on the juxtaposition of discrete spatial-temporal fragments in sequence, but on the moment-to-moment transformation of the mise-en-scène and on the arrangement of multiple time values in a single space. We may say, consequently, that the shot no longer denotes a united space and time but the potential for multiple times – the history of a space.

Directed by Aleksandr Sokurov Director of Photography, Steadycam Operator Tilman Büttner Produced by Andrey Deryabin, Jens Meurer, Karsten Stöter Screenplay by Anatoly Nikiforov, Aleksandr Sokurov Design Visual Concept and Principal Image Aleksandr Sokurov Music Performed by Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra Conducted by Valery Gergiev Original Score Sergey Yevtushnko Presentation of Hermitage Bridge Studio, Egoli Tossell Film AG

Cast Sergei Dreiden…. The Stranger - The Marquis de Custine, Maria Kuznetsova…. Catherine the Great, Leonid Mozgovoy…. The Spy, Mikhail Piotrovsky…. Himself (The Hermitage Director), David Giorgobiani…. Orbeli, Aleksandr Chaban…. Boris Piotrovsky, Tamara Kurenkova…. Herself (The Blind Woman)…. Maksim Sergeyev…. Peter the Great, Vladimir Baranov…. Nicholas II, Anna Aleksakhina…. Alexandra Fyodorovna, Wife of Nicholas II, Aleksandr Razbash…. Military Official

Notes:

[i] The biographical details included in this paragraph were taken from Aleksandr Sokurov’s official site, Island of Sokurov, which is overall an extraordinary resource on the director’s life and his body of work.

[ii] This last anecdote is included in Knut Elstermann’s fine documentary on the film’s making, In One Breath: Alexander Sokurov's Russian Ark (2003), which Wellspring featured on its DVD release of the film from that same year.

[iii] In terms of the critical response to Russian Ark, few if any of the director’s films have been as widely praised in the U.S.: it is, for instance, the only of the director’s films to have been reviewed by Roger Ebert, who gave the picture four stars (out of four) for his Chicago Sun-Times column. Likewise, art house-minded critics Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader) and J. Hoberman (The Village Voice) both named the film as one of the year’s “ten best” in 2002. In addition, Russian Art is also the director’s only box office success, grossing a respectable $2,326,979 during its U.S. theatrical run, including an impressive $29,022 opening tally on two screens in December of 2002 (courtesy of Box Office Mojo). To date, Russian Ark has earned more than $6.5 million worldwide, of which forty-five percent has been earned in the United States, making it the seventy-ninth highest grossing foreign language film in this country’s history. These numbers are all the more impressive when one considers that Father and Son (2004), Sokurov’s most recent film to earn an American theatrical release – also courtesy of Wellspring – has yet to earn $40,000. On the contrary, the director’s highly-acclaimed biography of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, The Sun (2005) – Cahiers du Cinema’s number one film of the year – remains undistributed. Surely, The Sun’s inability to secure U.S. distribution emphasizes the void left by Wellspring’s disappearance from the American theatrical landscape.

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

Friday, March 23, 2007

New Film: Offside

Jafar Panahi's Offside, the Iranian director's fifth feature, and the fifth to be banned in his home country, arrives in New York approximately twelve hours in advance of his President Ahmadinejad's scheduled arrival. This accident makes Offside perhaps the most timely New York premiere this spring, as the film extends Panahi's on-going account of social injustices -- particularly those against women -- in modern-day Iran. (That is, as we await the UN-sanctioned demagoguery of a world leader who has repeated voiced his desire to eliminate Israel and to eradicate the Jewish people from the face of the earth.)

In Panahi's latest, we glimpse the everyday injustices of Ahmadinejad's theocracy, where women are prevented from attending live sporting events, including Iran's final 2005 World Cup qualifier against Bahrain. Following a title that informs the spectator of this detail, as well as a second caption which claims that much of the film was shot at the stadium during said event, Panahi introduces us to an angry, albeit concerned father who is heading to the event to locate his daughter (before his sons can find her, whom he says would kill her). Subsequently, we are introduced to a female in disguise on a nearby bus, who we assume is the very girl noted above. As it will later turn out, she is not, though Panahi's film commences with following her attempts to enter the stadium. Therefore, it might be said that there is a certain interchangeability between the girls owing to their shared condition.

This young woman is immediately discovered, however, and is subsequently penned in with a group of her fellow male impersonators, just outside the stadium walls. As such, Panahi invents a formal analogue in the small visible cell positioned against the polyphonic off-screen stadium: that is, these young women, prevented from experiencing the public sphere on an equal basis with men, occupy a marginal space in relation to the larger, connoted off-camera space. Moreover, Panahi's utilization of tightly-framed mobile long takes further reinforces this dialectical relationship between theoretically separate on and off-camera spaces.

Of course, Panahi's use of long takes also succeeds in producing a facsimile of real time that has been the director's clearest stylistic device from his debut feature The White Balloon (1995). Here, the time of Offside is basically consubstantial with that of the game, concluding soon after the result is announced with the soldiers and the women celebrating in the nocturnal streets. (The game begins in late afternoon with Panahi charting the evening's transition to dusk.) In fact, within this coda, Pahani offers a glimpse of hope that is not unwarranted otherwise, provided his characterizations of the soldiers who guard the girls. While unwilling to break the law themselves, the soldiers seem to possess at least a flicker of sympathy. Hence, it might be said -- particularly when one considers the rebellion of the young women additionally -- that there is a reformative impulse in the people, even if the state remains irredeemably arcane.

In short, Offside continues Panahi's interrogation of Iranian social realities, culminating in another major work to stand beside his earlier highlights The White Balloon, The Circle (2000) and Crimson Gold (2003). However, unlike the first and third features listed above, Panahi's mentor Abbas Kiarostami did not pen the screenplay, which may account for an uncharacteristically underlined moment of psychological causality late in the film. Apart from this revelation, however, Offside remains a strong inheritor to the master's tradition, and once again confirms Panahi's status as Iran's greatest active filmmaker not named Kiarostami.

Monday, March 19, 2007

New Exhibitions: Tacita Dean / Spanish Painting / Gordon Matta-Clark

"All arts are founded on man's presence; only in photography do we enjoy his absence."

-Andre Bazin

Tacita Dean's Kodak (2006) joins James Benning's Ten Skies (2004) and Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub's These Encounters of Theirs (2006) as one of the finest new films to screen in New York thus far this year. Add to these works of the experimental (primarily non-narrative) cinema Film Comments Selects highlight Colossal Youth (Pedro Costa, 2006) and the structuralist-influenced April opening Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006), and one begins to wonder whether narrative cinema isn't beginning to fall further behind its avant-garde and poetic counterparts qualitatively. After such a lackluster year for Hollywood, such a claim does not seem as far-stretched as it might otherwise. Even the mid-majors have shown this turn with Michel Gondry's The Science of Sleep (2006). Of course, none of those films listed at the outset, in addition to Costa's, have or ever will receive anything approaching commercial distribution.

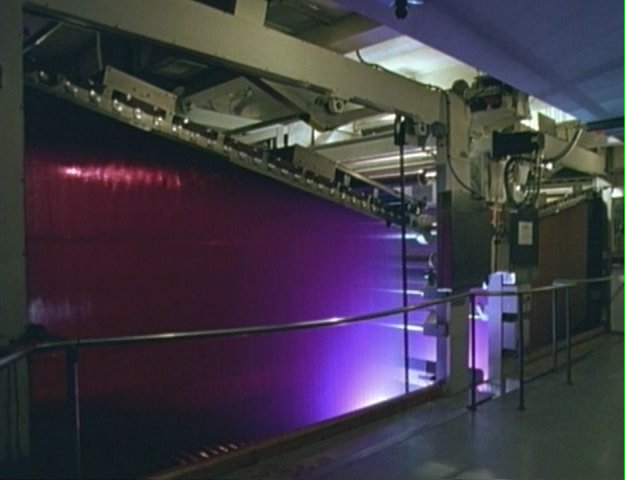

Fortunately, the Guggenheim New York is currently screening two of Tacita Dean's 16mm works, including the 40-plus minute Kodak, as part of its supplementary exhibition, The Hugo Boss Prize 2006: Tacita Dean. Kodak features footage of one of the eponymous film company's factories shot after Dean learned that this manufacturer of her 16mm medium was slated to close. Utilizing that same format, Kodak makes an argument for her medium's specificity and superiority over digital technologies in its registration of sensuous tones (particularly yellows, royal blues, turquoise/sea-greens and pink-tinted purples) in exceedingly low light. Dean's spare lighting often adorns empty corridors, which draw attention to film's post-human character -- that is as an indexical medium. This quality is similarly evident in Kodak's emphasis on the translucent material, which likewise underscores the medium's fragility. Indeed, this is the ultimate meaning that inheres within Kodak: namely, of a medium that is ceasing to exist, both in its lack of production and in the instability of the format itself. This eulogistic sense is suggested further in the concluding images of factory waste on the wet mill floor.

While the Tacita Dean exhibit occupies only a single room within the museum, the remaining non-permanent galleries are devoted to the epic Spanish Painting from El Greco to Picasso: Time, Truth, and History. As I may still write on the exhibition elsewhere, my comments will remain of necessity cursory. Suffice it to say of the enormous showcase, then, that while Spanish Painting does not break new ground, it does have the virtue of clarifying the unity of the Spanish visual tradition, and particularly the titular Picasso's self-conscious revisionism vis-a-vis his national context. In the end, if Picasso's art demonstrates the greatest dexterity, Goya's emerges as perhaps the most influential, Velázquez's the ultimate achievement in his nation's plastic tradition and El Greco's and Miro's the most respectively singular. It is worth noting that the exhibition is arranged by theme with many of the newer works (especially Picasso's) hanging beside those pieces that served as inspiration, either directly or indirectly.

For someone who is better versed in El Greco, Goya and Picasso, the opportunity to see such a large number of Velázquez's again -- many of which are on loan from the Prado -- serves to reinforce his preeminent stature, at least in this author's opinion: that is, as one of the oil medium's greatest practitioners, perhaps even the equal of Rembrandt himself. To be terse, Velázquez appears in Spanish Painting to be his art's greatest humanist: in the superlative "Don Sebastián de Morra" (ca. 1643-4) for example, the painter's representation of the little person secures the full weight of his subject's sadness, deriving as it does from his physical limitations -- both his height and his meaty hands. (A second similarly socially-themed highlight is Goya's "The Young Woman (The Letter)," after 1812, which limns the aristocratic subject concretely, while her servant and the workers behind her are all represented without this same clarity.) That is, Velázquez -- and Goya -- emphasize the social, whereas Rembandt's focus is the spiritual. To put it differently, Velázquez's subjects lack the souls that are the focus of his Dutch counterpart's art. Again, for Velázquez, it is their position within a social system and the impact that this has on their psychology -- to say nothing of his preoccupation with their garment's textures (Velázquez's painting, at its most assured, approaches a second sense, that of the creation of touch) and the medium itself, which all combine to forge the essence of his art.

Fifteen blocks to the south, The Whitney Museum of American Art is currently exhibiting the "anarchitecture" of Gordon Matta-Clark. Again, to be brief, Matta-Clark, son of Surrealist painter Roberto Matta, is perhaps best known for his incisions cut into abandoned or condemned structures, such as a pair of late 17th century homes (in "Conical Intersect") situated beside Paris's Centre Pompidou, or his 1974 "Splitting" where he does exactly that to a one-family home. In summary, Matta-Clark's art aids his spectator in securing a new perspective in viewing familiar locations, while offering substantive social and psychological ramifications: to the former, they assist us in understanding how people live together in cities, while the latter indicates both a formalization of Matta-Clark's broken home, and even more compellingly, his twin brother's suicide.

In terms of his media, since his art is by its definition ephemeral -- buildings immediately prior to their demolishing -- Matta-Clark portrayed his sites in both photographs and films. In so doing, Matta-Clark offers an analogy between his activity ("to clarify our personal awareness of place") and the process of representing the three-dimensional in two dimensions (namely, of finding a method to explode the spatial barriers inherent on said format). Thus, there is a rigor to match the artist's ambition, marking Matta-Clark as an exceedingly significant post-war American artist.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

New Film: Zodiac & The Lives of Others

David Fincher's Zodiac shoulders what might have been an insurmountable obstacle to its success as a thriller -- the fact that the true crime case upon which the film is based remains unsolved. Nevertheless, the director's latest serial killer picture secures a tension, though it is less connected to the police's investigation -- as of course its outcome is common knowledge -- than it is to amateur Robert Graysmith's (Jake Gyllenhaal as the author of the film's original non-fiction source) subsequent intervention. As Graysmith states when his wife (Chloë Sevigny) questions his motivation, he wants know to look into the eyes of the killer and to know that he is guilty. By this point, this is all that we as spectators want as well (or at least to know the murder's identity, obviously). And much to the credit of Fincher and his screenwriter James Vanderbilt, we become as convinced of a particular suspect's guilt as does Graysmith. Indeed, Fincher and Vanderbilt's control of circumstantial evidence ultimately points to the aforesaid suspect, even as we are compelled to at least wonder about the various other leads that Graysmith pursues.

To defer suspense until the film's second part -- that is, to transfer it onto the question of the killer's identity -- we are led to share in our degree of knowledge with the San Francisco P.D. (and especially its lead investigators Mark Ruffalo and Anthony Edwards) and the city's newspaper staff (where Gyllenhaal and Robert Downey Jr.'s Paul Avery work; the latter is another contribution to Downey Jr.'s drug-fueled persona -- cf. A Scanner Darkly, 2006) to which the Zodiac killer sends his encrypted missives. It is only after the investigation effectively concludes that Fincher and Vanderbilt begin to reveal the missteps of inter-departmental communication that assured the investigation's failure. As such, Zodiac offers a cogent account of this unsolved case and its likely perpetrator, and also a viable reason for its remaining unresolved.

Ultimately, Zodiac is less a sordid true crime case than it is a portrait of how these notorious murders remained unsolved. In other words, Zodiac is not Se7en (1995) -- not to imply that the earlier film has any basis in reality -- though it does share some of its tropes: perhaps the clearest example is the sparely lit, squirrel-infested trailer of one of the picture's suspects. Otherwise, many of Fincher's voluminous spaces feature visible overhead florescent lighting. Together, it again becomes clear, as it was in Se7en that the particularity of Fincher's style can be located in his modulations of (moody) lighting. Spatially, Fincher composes many of his shots horizontally across his wide screen.

Less obvious for any specific visual tropes, with the possible exception of occasionally distracting instances of rack focus, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen) offers another example of dubious recent history, albeit in fictionalized form. The recently Oscar-feted The Lives of Others -- the German picture was an upset winner in the 'best foreign language picture' category -- gives an account of one Stasi officer's (Michael Haneke axiom Ulrich Mühe) increasing disaffection with the GDR's practice of surveillance, though not on principle but rather by virtue of its abuses.

After one of East Germany's only loyal artists is placed under full surveillance as per a leading official's romantic interest in his actress lover, Stasi officer Wiesler begins his sabotage of the process, allowing the disenchanted writer and his compatriots to produce an anti-GDR tract that emphasizes the high incidence of suicide in the former state. Thus, Henckel von Donnersmarck limns a portrait of the GDR that both articulates the ubiquity of the state's crimes and also suggests the goodness and the courage of some of its citizenry. While of course both are undeniable, the filmmakers' emphasis upon the good Stasi provides a certain cover to those who may have been complicit; like De Gaulle's France in the postwar period, The Lives of Others indicates a move toward a revisionist, heroic history.

If it could be argued therefore that The Lives of Others presents a somewhat suspect glimpse at Germany's recent past, Henckel von Donnersmarck's direction of suspense leaves little to be desired. For example, the German director's staging of the climactic scene with all emphasis transferred onto a single feature of the architecture is worthy of and influenced by the 'Master of Suspense.' Then again, Henckel von Donnersmarck's assured direction of such sequences is accompanied by inclusions of passages that reiterate what the action has already made clear -- as with the overly distended conclusion. (The Lives of Others is nothing if not middle-brow.) Even so, the film's heart-warming final revelation, however overblown, achieves an undeniable emotional resonance.

To defer suspense until the film's second part -- that is, to transfer it onto the question of the killer's identity -- we are led to share in our degree of knowledge with the San Francisco P.D. (and especially its lead investigators Mark Ruffalo and Anthony Edwards) and the city's newspaper staff (where Gyllenhaal and Robert Downey Jr.'s Paul Avery work; the latter is another contribution to Downey Jr.'s drug-fueled persona -- cf. A Scanner Darkly, 2006) to which the Zodiac killer sends his encrypted missives. It is only after the investigation effectively concludes that Fincher and Vanderbilt begin to reveal the missteps of inter-departmental communication that assured the investigation's failure. As such, Zodiac offers a cogent account of this unsolved case and its likely perpetrator, and also a viable reason for its remaining unresolved.

Ultimately, Zodiac is less a sordid true crime case than it is a portrait of how these notorious murders remained unsolved. In other words, Zodiac is not Se7en (1995) -- not to imply that the earlier film has any basis in reality -- though it does share some of its tropes: perhaps the clearest example is the sparely lit, squirrel-infested trailer of one of the picture's suspects. Otherwise, many of Fincher's voluminous spaces feature visible overhead florescent lighting. Together, it again becomes clear, as it was in Se7en that the particularity of Fincher's style can be located in his modulations of (moody) lighting. Spatially, Fincher composes many of his shots horizontally across his wide screen.

Less obvious for any specific visual tropes, with the possible exception of occasionally distracting instances of rack focus, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen) offers another example of dubious recent history, albeit in fictionalized form. The recently Oscar-feted The Lives of Others -- the German picture was an upset winner in the 'best foreign language picture' category -- gives an account of one Stasi officer's (Michael Haneke axiom Ulrich Mühe) increasing disaffection with the GDR's practice of surveillance, though not on principle but rather by virtue of its abuses.

After one of East Germany's only loyal artists is placed under full surveillance as per a leading official's romantic interest in his actress lover, Stasi officer Wiesler begins his sabotage of the process, allowing the disenchanted writer and his compatriots to produce an anti-GDR tract that emphasizes the high incidence of suicide in the former state. Thus, Henckel von Donnersmarck limns a portrait of the GDR that both articulates the ubiquity of the state's crimes and also suggests the goodness and the courage of some of its citizenry. While of course both are undeniable, the filmmakers' emphasis upon the good Stasi provides a certain cover to those who may have been complicit; like De Gaulle's France in the postwar period, The Lives of Others indicates a move toward a revisionist, heroic history.

If it could be argued therefore that The Lives of Others presents a somewhat suspect glimpse at Germany's recent past, Henckel von Donnersmarck's direction of suspense leaves little to be desired. For example, the German director's staging of the climactic scene with all emphasis transferred onto a single feature of the architecture is worthy of and influenced by the 'Master of Suspense.' Then again, Henckel von Donnersmarck's assured direction of such sequences is accompanied by inclusions of passages that reiterate what the action has already made clear -- as with the overly distended conclusion. (The Lives of Others is nothing if not middle-brow.) Even so, the film's heart-warming final revelation, however overblown, achieves an undeniable emotional resonance.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

New Film: Half Nelson & These Encounters of Theirs

The Jus Rhyme of this year's Academy nominated films -- that is "politically aware and socially responsible" with a graduate-level ethnic studies tool box -- Ryan Fleck's Half Nelson confronts its audience with its political imperatives: namely, to generate consciousness through the film's inhabitation and dissection of its structuring "dialectics." This is to say that Fleck's classroom-centered picture (and a history classroom at that) adheres to a Marxist model of conflict-based historiography, which is disseminated primarily in Ryan Gosling's homilies on topics such as "turning points." (Actually, Gosling's Dan Dunne is at one point asked whether or not he is a Communist to which he redirects the conversation.) His students, for their part, relate moments of historical tragedy and resistance through direct address, thereby reaffirming that purpose of these lessons are not only to instruct the film's characters but to teach its spectators as well.

The Jus Rhyme of this year's Academy nominated films -- that is "politically aware and socially responsible" with a graduate-level ethnic studies tool box -- Ryan Fleck's Half Nelson confronts its audience with its political imperatives: namely, to generate consciousness through the film's inhabitation and dissection of its structuring "dialectics." This is to say that Fleck's classroom-centered picture (and a history classroom at that) adheres to a Marxist model of conflict-based historiography, which is disseminated primarily in Ryan Gosling's homilies on topics such as "turning points." (Actually, Gosling's Dan Dunne is at one point asked whether or not he is a Communist to which he redirects the conversation.) His students, for their part, relate moments of historical tragedy and resistance through direct address, thereby reaffirming that purpose of these lessons are not only to instruct the film's characters but to teach its spectators as well.Even so, Fleck's narrative refuses to glorify the consciousness-generating Mr. Dunne. Principally, Half Nelson's reversal of generic norms emerges when it is revealed that Gosling's character smokes crack -- make no mistake, Fleck is endeavoring to problematize the binary between white and black where smoking crack is a behavior of the latter. One of his students, Drey (Shareeka Epps), discovers the altered educator in the ladies room after her basketball game. As we soon learn, Drey's brother is incarcerated, and his business associate, Anthony Mackie as Frank, is a drug dealer with both proprietary feelings for the vulnerable 13 year-old and also designs to involve her in the business. Ultimately, she acquiesces, though her subsequent exposure to Dunne smoking rock ends her foray into dealing.

For his part, Dunne's use of this stigmatized substance can be explained for its facility in interrogating the racial dialectical that shapes the picture's context. That he uses drugs at all reflects an attempt "to get by," to somehow satiate the feelings of injustice that undoubtedly consume Fleck's hero. At the same time, Gosling's Dunne does engage with the social inequities that plague society. On the micro level, this is reflected in his attempts to protect Drey from Frank, which he prefaces with the knowledge that he "should be the last person to say this." However, owing to the film's project of unmooring the dialectics it preaches, Frank also warns Drey to be cautious of her base-head teacher.

Ultimately, Fleck's program seeks to reconstitute social systems synthetically, by achieving synthesis through the opposition of thesis and anti-thesis. This comes into the play both in the relationship between Dunne and Drey and also in its interrogation of elements of African-American culture (be it in the language he uses, the books he reads or the more structural articulation of Malcolm X's public proclamations). With regard to the first of these, Drey's epiphany occurs when she sees her teacher in the throws of the substance -- therefore awakening her to the consequences of dealing -- while Fleck needs the help of his younger student to clean up, which provides the film with its culminating two of the pair on a couch. As such, Fleck appears to flip the conventional assumed direction of paternalistic assistance, though it is likewise clear that in Half Nelson this inversion of trope serves strictly discursive purposes and thus partakes in the same stereotypes. In other words, Half Nelson makes paternalism palatable by artfully reversing its coordinates.

Ultimately, Fleck's program seeks to reconstitute social systems synthetically, by achieving synthesis through the opposition of thesis and anti-thesis. This comes into the play both in the relationship between Dunne and Drey and also in its interrogation of elements of African-American culture (be it in the language he uses, the books he reads or the more structural articulation of Malcolm X's public proclamations). With regard to the first of these, Drey's epiphany occurs when she sees her teacher in the throws of the substance -- therefore awakening her to the consequences of dealing -- while Fleck needs the help of his younger student to clean up, which provides the film with its culminating two of the pair on a couch. As such, Fleck appears to flip the conventional assumed direction of paternalistic assistance, though it is likewise clear that in Half Nelson this inversion of trope serves strictly discursive purposes and thus partakes in the same stereotypes. In other words, Half Nelson makes paternalism palatable by artfully reversing its coordinates.At this point, I would feel remiss were I not to mention the film's performances, which remain its principle popular claim to fame. At the center, Ryan Gosling's Mr. Dunne achieves an understatement that seems to be of a type with the film's iteration of nuance (that is, in laying claim to the competing factors that forge personality and finally humanity). Similarly, Epps and Mackie also exhibit this tendency toward underplaying that mute a narrative that is in other ways less measured -- as in again the historical lessons of Mr. Dunne's class. As per Mr. Fleck's visual style, the director sustains a like staidness throughout, composing his spaces in static set-ups that intimate a certain unwillingness to intercede and on the most practical level serve to represent the subtleties of his performances.

A film that forges a very different relationship between camera and performance is the similarly political final collaboration between husband-and-wife filmmaking team, Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet. These Encounters of Theirs (2006) begins its series of Cesare Pavese dialogues by framing its two actors with their backs to the camera as they stand on the edge of a Tuscan hillside. The pair, whom we only see speaking to each other subsequently (as they turn their heads partially to address one another) each enunciate in loud, unmodulated voices. As we soon discover, they are both gods, albeit gods dressed in inexpensive modern clothing. They are also gods whose claim to human worship have become increasing tenuous; to be sure, it is made quite clear that humanity does not need these immortal beings. Hence, it becomes apparent that Straub and Huillet are de-mystifying their inherently spiritual subject matter both in the specificity of the conversations themselves and also by making beings to appear as people in a relatively familiar setting. Indeed, there is a certain currency between these dialogues and Eisenstein's montage of cross-cultural idols in October (1928).

A film that forges a very different relationship between camera and performance is the similarly political final collaboration between husband-and-wife filmmaking team, Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet. These Encounters of Theirs (2006) begins its series of Cesare Pavese dialogues by framing its two actors with their backs to the camera as they stand on the edge of a Tuscan hillside. The pair, whom we only see speaking to each other subsequently (as they turn their heads partially to address one another) each enunciate in loud, unmodulated voices. As we soon discover, they are both gods, albeit gods dressed in inexpensive modern clothing. They are also gods whose claim to human worship have become increasing tenuous; to be sure, it is made quite clear that humanity does not need these immortal beings. Hence, it becomes apparent that Straub and Huillet are de-mystifying their inherently spiritual subject matter both in the specificity of the conversations themselves and also by making beings to appear as people in a relatively familiar setting. Indeed, there is a certain currency between these dialogues and Eisenstein's montage of cross-cultural idols in October (1928).Nevertheless, by initially refusing the spectator a view of the speakers' mouths, Straub and Huillet reposition the voice as a mystical object that in fact confirms a presence while remaining invisible to the viewer. Of course, the voice is always de-spatialized (and unseeable) in this manner, but in the filmmakers' intentional introduction of their dialogues thusly, they remind of us of this essential property of sound -- of its invisible presence. It is only later that these sounds are embodied, that they are grounded in the physical presence of a human figure. As such, Straub and Huillet while removing the gods' mystery in one respect, are reintroducing a form of magic in another -- again, by focusing our attention on the voice's lack of spatialization. In other words, the filmmakers provide an analogy for representing the immaterial in cinema through their gradual reunification of voice and body, even if this analogy reappropriates the miraculous for cinema itself, and its accorded materiality.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

New Film: Ten Skies

In the spirit of tomorrow evening's celebration of the 79th Academy Awards, let me say a few words on the best new(ish) American film I have seen in the past twelve months, James Benning's Ten Skies (2004). A companion to his similarly constructed 13 Lakes (also 2004), Ten Skies is assembled of ten static ten minute shots of Val Verde, California skies. Each is composed of continually changing cloud formations, which emit an enormous degree of variation from one set-up to the next. For instance, Benning's film begins with a relatively clear blue sky occupied by a pair of intersecting jet trails that gradually disappear out of the top of the frame. In his second set-up, the film shifts to fluffy cumulus clouds with dark shading that start to resemble trompe l'oiel paintings of the same subject. In the third, Benning's color palette shifts to a grayish blue green supporting fast moving blanched clouds. In other words, Benning's film offers substantial variation in its color schema from one sky to the next and even within each shot.

Certainly, the moment-to-moment transformations of his aeriel views is among the principle subjects of Ten Skies. Then again, not only does Benning's film not require its viewers' continued attention, but in fact it encourages distraction. That is, with the renewal of viewer attention after moments of intellectual drift -- a mechanism built into his discursive structure -- Benning's film produces drastic changes that seem unthinkable after even the briefest of intervals. Further, the film's alternation from one set-up to the next eventually produces a sort of suspense in the disclosure of the following scene, even as a drama can be produced from a cloud's gradual overtaking of the full frame or in an airplane's inching toward the image's edge.

Speaking of the edge, as with 13 Lakes, Ten Skies adheres to Andre Bazin's notion of the frame as a mask, calling attention equally to what remains outside the visual field. Indeed, it is not simply the passage of cloud formations into and out of the frame, but even more the non-sync off-camera soundscapes that transform Benning's spaces from their minimal enframed sections to a maximal combination of on and off camera fields.

Therefore, Benning articulates his medium's spatial ontology (with its relation to the frame), as he also underscores the perpetual remaking of space that separates his medium from the other visual arts. Then again, it is less these didactic functions than the aesthetic properties that adhere in his images which truly recommend Ten Skies. Specifically, it is his panchromatic palette and the variations in textures that these distinctions produce, which mark the artistic achievement of Benning's film. For example, one of the film's darker skies figures a second, silky veil in the fore of the larger climatic formation. Separately, the film's concluding pairing of gray and deep blue ultimately yields a preternatural blue that begins to look like something quite distinct from nature. Indeed, Benning's sky-scapes secure an abstract patterning before our eyes with a hard, mineral texture that ultimately loses even this tentative visual grounding. (It is worth noting that Benning's choice of 16mm is essential to attaining the effects that distinguish Ten Skies.)

In the end, Ten Skies encourages a keener vision of not only cinema but of nature itself. It compels its spectator to notice more subtle variations in color, texture and movement than we are accustomed to seeing. In other words, Benning (to paraphrase an earlier purpose statement by the filmmaker) is teaching his viewers to see like artists see. Moreover, Ten Skies, again like 13 Lakes, represents a sustained examination of cinema's unique character, locating its specificity in its capacity to represent movement and also its construction of a space greater than the visual field. Thus Ten Skies once again calls us to see anew, though in this latter case it is cinema rather than nature which the filmmaker's lesson emphasizes.

Certainly, the moment-to-moment transformations of his aeriel views is among the principle subjects of Ten Skies. Then again, not only does Benning's film not require its viewers' continued attention, but in fact it encourages distraction. That is, with the renewal of viewer attention after moments of intellectual drift -- a mechanism built into his discursive structure -- Benning's film produces drastic changes that seem unthinkable after even the briefest of intervals. Further, the film's alternation from one set-up to the next eventually produces a sort of suspense in the disclosure of the following scene, even as a drama can be produced from a cloud's gradual overtaking of the full frame or in an airplane's inching toward the image's edge.

Speaking of the edge, as with 13 Lakes, Ten Skies adheres to Andre Bazin's notion of the frame as a mask, calling attention equally to what remains outside the visual field. Indeed, it is not simply the passage of cloud formations into and out of the frame, but even more the non-sync off-camera soundscapes that transform Benning's spaces from their minimal enframed sections to a maximal combination of on and off camera fields.

Therefore, Benning articulates his medium's spatial ontology (with its relation to the frame), as he also underscores the perpetual remaking of space that separates his medium from the other visual arts. Then again, it is less these didactic functions than the aesthetic properties that adhere in his images which truly recommend Ten Skies. Specifically, it is his panchromatic palette and the variations in textures that these distinctions produce, which mark the artistic achievement of Benning's film. For example, one of the film's darker skies figures a second, silky veil in the fore of the larger climatic formation. Separately, the film's concluding pairing of gray and deep blue ultimately yields a preternatural blue that begins to look like something quite distinct from nature. Indeed, Benning's sky-scapes secure an abstract patterning before our eyes with a hard, mineral texture that ultimately loses even this tentative visual grounding. (It is worth noting that Benning's choice of 16mm is essential to attaining the effects that distinguish Ten Skies.)

In the end, Ten Skies encourages a keener vision of not only cinema but of nature itself. It compels its spectator to notice more subtle variations in color, texture and movement than we are accustomed to seeing. In other words, Benning (to paraphrase an earlier purpose statement by the filmmaker) is teaching his viewers to see like artists see. Moreover, Ten Skies, again like 13 Lakes, represents a sustained examination of cinema's unique character, locating its specificity in its capacity to represent movement and also its construction of a space greater than the visual field. Thus Ten Skies once again calls us to see anew, though in this latter case it is cinema rather than nature which the filmmaker's lesson emphasizes.

Sunday, February 18, 2007

Correspondences from Sixty-Eight!: The Structure of Crystal + Early Garrel

Zanussi's The Structure of Crystal compares most closely perhaps to another 1969 classic, Eric Rohmer's My Night at Maud's, though Zanussi has replaced the latter film's theological conversations with those of physics, and particularly the titular crystals. Then again, Zanussi has likewise diverged from Rohmer in that his conversations contain explicit ellipses: when the picture's two physicists begin discussing the historical concept of "infinity," for instance, the music on the soundtrack swells, even as stills of the various authors and books discussed grace the screen. In this way, the director is both condensing what might not be a terribly interesting conversation to most, even as he suggests that the film contains subject matter that cannot be directly expressed on screen (be it for both political and pyschological reasons). The Structure of Crystal is in fact a film that is very much concerned with interiority.

Indeed, The Structure of Crystal is also the second film in the series -- after Birds, Orphans and Fools -- to present a menage-a-trois, though here it is far more understated than in the high-key Slovak film. Again, these thoughts and desires burn, or at least smolder under the surface. Beyond this interest in the mind, a second point of comparison is the director's countryman Roman Polanski's Cul-de-sac (1965), wherein an explicitly existentialist sensibility and thought has been imparted in the picture. In The Structure of the Crystal it is the twin preoccupations of engagement and the feeling of waiting (for something to happen) that marks Zanussi as an heir to Beckett, Camus, Sartre, et al. -- the expansive horizons of the films' exteriors underscore the accompanied sense of isolation. To be sure, The Structure of Crystal is marked by dead time, which is occupied not only by the aforementioned conversations, but also by moments of play and levity, including a mimed athletic competition performed by the two physicist leads, a visit to town and to an erotic film, which is preceded by a newsreel depicting a shiny factory, and recounted later with comic visuals. Ultimately, it was the Sixty-Eight! film that I was most hoping wouldn't end.

***

While I can't also say this about Philippe Garrel's Le Révélateur (1967), I would say that at the very least that the nineteen year-old Garrel's sixty-minute silent possesses the same visual grace -- visible in the low contrast deep blacks and neon whites of his palette -- as his more recent, acclaimed Regular Lovers (2005). Actually, that recent Manhattan release could serve as a spiritual epitaph for Sixty-Eight!, and in a perfect world, would have closed the conference.Saturday, February 17, 2007

Correspondences from Sixty-Eight!: China is Near

Warning: the following post contains spoliers.

Five feature-length films and an additional five shorts into the festival, I have seen exactly three minutes of film dating to 1968 (Harun Farocki's The Words of the Chairman, which the program notes actually lists as 1967, so that number may in fact be zero). Yet, as a portrait of the era's convoluted radicalism, Sixty-Eight! has proven continually illuminating -- and I really don't mean that pejoratively. Friday night's closing offering, Marco Bellocchio's China is Near (La Cina è vicina, 1967), following a screening of Jean-Luc Godard's La Chinoise (also '67) again paired bedroom-themed political satire with Godard's fragmented ruminations on the state of the present. In the case of China is Near, Bellocchio's second feature, the satirical subject is not the sexually revolution, but rather Italian class dynamics. It is worth noting, parenthetically, that the director adopts a classical narrative structure, which in the midst of so many self-reflexive works, gives China is Near a vibrancy and timelessness lacking in the majority of the festival's remaining narrative offerings.

But, to the story itself, China is Near tells the story of Glauco Mauri's billionaire school teacher Vittorio (he's a member of the titled aristocracy, so don't let his c.v. fool you) who is drafted to run on the socialist ticket, even though he has failed to show any consistent political vision of his own. His recruitment riles loyal party man Carlo (Paolo Graziosi) who acts out his resentment by sleeping with Vittorio's spinster sister Elena (played by Elda Tattoli). This in turn drives Vittorio and Elena's maid, and Carlo's girlfriend, Giovanna (Daniela Surina) to couple with the overweight late thirty-something Vittorio. In fact, it is after this first round of sexual treachery that Bellocchio creates one of his finest set-pieces: the former working-class couple dress in silence in the hallway, as each has been expelled by their wealthy lover in order to keep up appearances.

Soon, we learn that Carlo has impregnated Elena, which leads the young man to ask the heiress to marry him; he confesses to Giovanna: "I like her, and her money -- I like her too." This series of events in turn compels Giovanna to ask Carlo to do the same for her, which he succeeds in doing (that is, Giovanna presents the unborn child as Vittorio's). In the meantime, an infuriated Elena demands that Vittorio arrange for her an abortion -- which proves unsuccessful after some bullying by Carlo -- and finally, that he expel both Carlo and Giovanna from their house. Finally, Vittorio showing an expected savvy attempts to persuade Carlo to take Giovanna as his wife -- both to fulfill his sister's wishes, and also to protect the woman he fears he defiled. Of course, this request echoes Giovanna's desire to marry Carlo which she had proclaimed at the film's beginning. Thus, Bellocchio would seem to be confirming the impossibility of social mobility, which the younger couple's plan had seemed destined to secure.

Then again, Bellocchio leads us to believe that Giovanna does end up marrying Vittorio, which is an intention he confesses during a political rally -- thereby making the act one of political expediency. At the same time, Carlo is shut out of the lives of both his children confirming again the rigidity of class dynamics, as well as providing the film with a more mythic register. (It is worth mentioning that while Giovanna does herself escape her class, which in a way would seem to blunt the satire's impact, though she is at the same time a beautiful young woman which is surely a tried-and-true ticket to prosperity.) In the end, the wealthy control all the power and exercise it as they feel fit; indeed, the project of socialism is shown to be fruitless as it relies on the good graces of the upper class, which of course it does not extend. As Millicent Marcus noted in her introduction: China is in fact not near. The revolutionary politics of that state are far removed from the class collaborations of the Italian system, which invariably end poorly for those on the lower end. And certainly it doesn't help that the only character Bellocchio grants this political foresight is the third sibling of Vittorio and Elena, who doubles as an altar boy and political terrorist -- he does succeed in having sex with a young woman to awaken her class consciousness ,by the revealing to her the exploitative nature of the act; in painting "China is Near" on a wall (before being reprimanded by a police officer); and finally, in blowing up a toilet in the socialist party headquarters.

Five feature-length films and an additional five shorts into the festival, I have seen exactly three minutes of film dating to 1968 (Harun Farocki's The Words of the Chairman, which the program notes actually lists as 1967, so that number may in fact be zero). Yet, as a portrait of the era's convoluted radicalism, Sixty-Eight! has proven continually illuminating -- and I really don't mean that pejoratively. Friday night's closing offering, Marco Bellocchio's China is Near (La Cina è vicina, 1967), following a screening of Jean-Luc Godard's La Chinoise (also '67) again paired bedroom-themed political satire with Godard's fragmented ruminations on the state of the present. In the case of China is Near, Bellocchio's second feature, the satirical subject is not the sexually revolution, but rather Italian class dynamics. It is worth noting, parenthetically, that the director adopts a classical narrative structure, which in the midst of so many self-reflexive works, gives China is Near a vibrancy and timelessness lacking in the majority of the festival's remaining narrative offerings.

But, to the story itself, China is Near tells the story of Glauco Mauri's billionaire school teacher Vittorio (he's a member of the titled aristocracy, so don't let his c.v. fool you) who is drafted to run on the socialist ticket, even though he has failed to show any consistent political vision of his own. His recruitment riles loyal party man Carlo (Paolo Graziosi) who acts out his resentment by sleeping with Vittorio's spinster sister Elena (played by Elda Tattoli). This in turn drives Vittorio and Elena's maid, and Carlo's girlfriend, Giovanna (Daniela Surina) to couple with the overweight late thirty-something Vittorio. In fact, it is after this first round of sexual treachery that Bellocchio creates one of his finest set-pieces: the former working-class couple dress in silence in the hallway, as each has been expelled by their wealthy lover in order to keep up appearances.

Soon, we learn that Carlo has impregnated Elena, which leads the young man to ask the heiress to marry him; he confesses to Giovanna: "I like her, and her money -- I like her too." This series of events in turn compels Giovanna to ask Carlo to do the same for her, which he succeeds in doing (that is, Giovanna presents the unborn child as Vittorio's). In the meantime, an infuriated Elena demands that Vittorio arrange for her an abortion -- which proves unsuccessful after some bullying by Carlo -- and finally, that he expel both Carlo and Giovanna from their house. Finally, Vittorio showing an expected savvy attempts to persuade Carlo to take Giovanna as his wife -- both to fulfill his sister's wishes, and also to protect the woman he fears he defiled. Of course, this request echoes Giovanna's desire to marry Carlo which she had proclaimed at the film's beginning. Thus, Bellocchio would seem to be confirming the impossibility of social mobility, which the younger couple's plan had seemed destined to secure.

Then again, Bellocchio leads us to believe that Giovanna does end up marrying Vittorio, which is an intention he confesses during a political rally -- thereby making the act one of political expediency. At the same time, Carlo is shut out of the lives of both his children confirming again the rigidity of class dynamics, as well as providing the film with a more mythic register. (It is worth mentioning that while Giovanna does herself escape her class, which in a way would seem to blunt the satire's impact, though she is at the same time a beautiful young woman which is surely a tried-and-true ticket to prosperity.) In the end, the wealthy control all the power and exercise it as they feel fit; indeed, the project of socialism is shown to be fruitless as it relies on the good graces of the upper class, which of course it does not extend. As Millicent Marcus noted in her introduction: China is in fact not near. The revolutionary politics of that state are far removed from the class collaborations of the Italian system, which invariably end poorly for those on the lower end. And certainly it doesn't help that the only character Bellocchio grants this political foresight is the third sibling of Vittorio and Elena, who doubles as an altar boy and political terrorist -- he does succeed in having sex with a young woman to awaken her class consciousness ,by the revealing to her the exploitative nature of the act; in painting "China is Near" on a wall (before being reprimanded by a police officer); and finally, in blowing up a toilet in the socialist party headquarters.

Friday, February 16, 2007

Correspondences from Sixty-Eight!: Birds, Orphans and Fools + Slavic shorts

In my estimation, the point of Sixty-Eight! is to screen films exactly like Slovakian Juraj Jakubisko's Birds, Orphans and Fools (Vtackovia, siroty a blazni, 1969): that is, to uncover major works of art that have remained obscure to even the most knowledgeable of cineastes (even if the film again falls outside of the conference's '68 auspices, as have the other four shorts and two features that I have viewed thus far). Birds, Orphans and Fools begins innocently enough as an absurdist Jules et Jim (1962, François Truffaut) located in the ruins of a large manor -- that is, after a compulsory self-reflexive (read Godardian or Brechtian) interlude and a carnivalesque parade of outcast children and adults. At first a poly-amorousness rules, with the lead Yorick (Jirí Sykora) even remarking that he mast have been really drunk to end up in bed with a woman (Martha, the initially androgynous though exceptionally beautiful Magda Vásáryová). A third, Andrej (Philippe Avron) joins the couple and what proceeds seems to be a fairly standard page out of Vera Chytilová's Daisies (1966) anarchic playbook. However, with Yorick's shipment off to prison and his return as a normalized member of society replete with suit and tie, Jakubisko's narrative shifts courses revealing its position within the tradition of a conflated love-and-death that marks Luis Buñuel's narratives of sexual obsession -- i.e. El (1952), Diary of a Chambermaid (1964) or part one of Viridiana (1961). In fact, this last work remains an essential point of comparison for Birds..., particularly as Jakubisko's film seems to resurrect the idea of the lunatics running the asylum -- that is the breaking into the manor of the Spanish film and its occupancy in the Czechoslovakian one. Then again, Jakubisko's points-of-reference are not exclusively meta-cinematic: there is the immolation with its clear Vietnamese, anti-war implications, and perhaps more importantly still, the short cropped hair and the train ride with the Orthodox Jew, to say nothing of a number of lines of dialogue that all seem to reference the Holocaust. This last point seems especially pertinent as it gives existentialist weight to the 'eat, drink and be merry ethos' of the film's first three-quarters. However, as with I Am Curious - Yellow of the previous evening, love is not an emotion so easily contained by liberation politics.

If the above work has been the "discovery" of the fest to date, an earlier surprise addition rates as a close runner-up: Armenian Artavazd Peleshian's We (Menq, 1969). Described by Soviet specialist John MacKay as the Soviet Union's most important maker of avant-garde documentaries after Dziga Vertov, We seems to bear out that accolade, particularly in its remarkable capture of visual rhythms and textures. In one particularly striking overhead, an undulating crowd becomes viscous -- as in glutinous -- before our eyes. In another, Peleshian compares the sweaty, muscular physiques of workers with the towering stone mountains. Apart from We, the most impressive of the remaining works of experimental documentary may be Ivan Balad'a's Metrum (1967, Czechoslovakia), which compares closest, in my estimation to Jon Jost's rarely-screened London Brief (1997), though Balad'a's work achieves an exceptional visual richness manifesting in the beautiful flares of his Moscow underground locales.

If the above work has been the "discovery" of the fest to date, an earlier surprise addition rates as a close runner-up: Armenian Artavazd Peleshian's We (Menq, 1969). Described by Soviet specialist John MacKay as the Soviet Union's most important maker of avant-garde documentaries after Dziga Vertov, We seems to bear out that accolade, particularly in its remarkable capture of visual rhythms and textures. In one particularly striking overhead, an undulating crowd becomes viscous -- as in glutinous -- before our eyes. In another, Peleshian compares the sweaty, muscular physiques of workers with the towering stone mountains. Apart from We, the most impressive of the remaining works of experimental documentary may be Ivan Balad'a's Metrum (1967, Czechoslovakia), which compares closest, in my estimation to Jon Jost's rarely-screened London Brief (1997), though Balad'a's work achieves an exceptional visual richness manifesting in the beautiful flares of his Moscow underground locales.

Correspondences from Sixty-Eight!: Far From Vietnam & I Am Curious - Yellow

Yale University's Sixty-Eight! Europe, Cinema, Revolution? opened this evening with a pair of films preceding its year-specific subject. Far From Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam, 1967) represents the collaboration of legends Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda in the production of a pro-North Vietnamese tract, assembled from the filmmakers' documentary (and in some cases, fictional) footage. In a word, Far From Vietnam is propaganda, which in many cases raises more questions than it answers: for instance, what role were the Soviets and the Chinese playing in South-East Asia? Are the filmmakers overstating the Edenic, pre-industrial qualities of North Vietnam, etc.? Then again, Far From Vietnam's one-sided narrative should not be counted as a weakness: the picture never pretends to be anything other than what it is, agit. prop. And in this regard, which is to say on the level of the visceral, Far From Vietnam is powerful work, at least to the sympathetic; for the skeptical, Far From Vietnam can be a maddening experience.

Of course, none of this exactly speaks to its placement at the head of Sixty-Eight! While surely its inclusion suggests a precondition to the Leftist revolts of the following spring, and specifically to the currency of anti-war sentiments in France, Far From Vietnam seems better positioned as a work of our time, contextualizing Franco anti-Americanism in the Bush era. If anyone wants to say unequivocally that the current U.S. President lost the rest of the world, they may want to consult Far From Vietnam. Then again, a screening of Far From Vietnam might have also saved the right the trouble of worrying about whether or not Europe would support Bush's war. Actually, Far From Vietnam raises an even bigger question, though: whether a broad war can possibly sustain popular will at all in Western societies, now that television has made everything visible to the general public.

Far less fraught perhaps, but similarly political in its subject, the evening's second offering, Vilgot Sjöman's I Am Curious - Yellow (Jag är nyfiken - en film i gult, 1967) manifests even less connection to the conference's 1968 topic. Even so, Sjöman's notorious soft-core art film served as an excellent balance to the collaborative doc. Whereas, Far From Vietnam is rhetorically unambiguous, I Am Curious - Yellow instantiates a more measured approach to its topic. Here, Sweden's revolutionary sexual politics are interrogated in what one could only call a conservative fashion: early twenty-something protagonist Lena (Lena Nyman) experiences the consequences of her liberated sexuality -- namely, a broken-heart and venereal disease. Then again, given Sweden's extreme liberalization in the post-war period, it follows that its filmmakers would have to combat the deficiencies of their relativistic society, wherever they appear, with moralist rhetoric; basically, there was no space to satirize Swedish society on the left.

However, it is not simply in the relative conservatism of Sjöman's content that I Am Curious - Yellow balances Far From Vietnam, but indeed in its own admittance of contrary and contradictory perspectives. I Am Curious - Yellow utilizes a fictionalized direct, cinema-verité form that includes a spectrum of reactions, even if, ultimately, Sweden is portrayed as a nation largely lacking a class consciousness. Then again, the film's filmmaker-character (played by Sjöman himself) is as subject to his individual needs as are any of the anonymous Swedes on the street, of which the film's 'meta' structure is a reflection. That is, Sjöman reminds us of his role in constructing the explicit sexual content of the picture, and particularly in the pleasure he takes from watching his actors perform the acts. (And make no mistake, I Am Curious - Yellow truly does set the standard for explicit content in the European art cinema of the time.) Nevertheless, even if Sjöman's picture partakes in Sweden's extreme participation in the sexual revolution, his picture remains aware of its limitations, as his portrayal of Lena makes clear.

Of course, none of this exactly speaks to its placement at the head of Sixty-Eight! While surely its inclusion suggests a precondition to the Leftist revolts of the following spring, and specifically to the currency of anti-war sentiments in France, Far From Vietnam seems better positioned as a work of our time, contextualizing Franco anti-Americanism in the Bush era. If anyone wants to say unequivocally that the current U.S. President lost the rest of the world, they may want to consult Far From Vietnam. Then again, a screening of Far From Vietnam might have also saved the right the trouble of worrying about whether or not Europe would support Bush's war. Actually, Far From Vietnam raises an even bigger question, though: whether a broad war can possibly sustain popular will at all in Western societies, now that television has made everything visible to the general public.

Far less fraught perhaps, but similarly political in its subject, the evening's second offering, Vilgot Sjöman's I Am Curious - Yellow (Jag är nyfiken - en film i gult, 1967) manifests even less connection to the conference's 1968 topic. Even so, Sjöman's notorious soft-core art film served as an excellent balance to the collaborative doc. Whereas, Far From Vietnam is rhetorically unambiguous, I Am Curious - Yellow instantiates a more measured approach to its topic. Here, Sweden's revolutionary sexual politics are interrogated in what one could only call a conservative fashion: early twenty-something protagonist Lena (Lena Nyman) experiences the consequences of her liberated sexuality -- namely, a broken-heart and venereal disease. Then again, given Sweden's extreme liberalization in the post-war period, it follows that its filmmakers would have to combat the deficiencies of their relativistic society, wherever they appear, with moralist rhetoric; basically, there was no space to satirize Swedish society on the left.

However, it is not simply in the relative conservatism of Sjöman's content that I Am Curious - Yellow balances Far From Vietnam, but indeed in its own admittance of contrary and contradictory perspectives. I Am Curious - Yellow utilizes a fictionalized direct, cinema-verité form that includes a spectrum of reactions, even if, ultimately, Sweden is portrayed as a nation largely lacking a class consciousness. Then again, the film's filmmaker-character (played by Sjöman himself) is as subject to his individual needs as are any of the anonymous Swedes on the street, of which the film's 'meta' structure is a reflection. That is, Sjöman reminds us of his role in constructing the explicit sexual content of the picture, and particularly in the pleasure he takes from watching his actors perform the acts. (And make no mistake, I Am Curious - Yellow truly does set the standard for explicit content in the European art cinema of the time.) Nevertheless, even if Sjöman's picture partakes in Sweden's extreme participation in the sexual revolution, his picture remains aware of its limitations, as his portrayal of Lena makes clear.

Thursday, February 15, 2007

This Weekend In New Haven

Sixty-Eight! Europe, Cinema, Revolution?

A Film Festival and Conference at Yale University

Thursday, February 15 to Saturday, February 17, 2007

Whitney Humanities Center, 53 Wall St., New Haven, CT

Sixty-Eight! Europe, Cinema, Revolution? will focus on the New Wave cinemas of Eastern and Western Europe leading up to and in the aftermath of the political showdowns of 1968. The European Studies Council, along with the Film Studies Program and the Department of the History of Art, has organized the festival around a wide variety of films from many countries, from little-known gems and avant-garde shorts to recognized cinematic classics. The festival will interlace feature films, documentaries, and experimental films with introductions by scholars and critics from a range of disciplines, and informal panels and open discussions. A complete list of participants and details may be found at http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/europeanstudies/1968

Thursday, February 15

7:00pm Far From Vietnam (Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, France, 1967, 16mm)

9:30pm I Am Curious - Yellow (Vilgot Sjoman, Sweden, 1967, 35mm)

Friday, February 16

9:00am Cinegiornali liberi (Cesare Zavattini et al., Italy, 1968, 16mm)

Classe de lutte (Les Groupes Medvedkine de Besancon, France, 1968, 16mm)

La reprise du travail aux usines Wonder (Etats generaux du cinema, France, 1968, DVD)

10:45am Discussion: Giorgio De Vincenti (Universita di Roma-III), Michael Denning (Yale), Annette Michelson (Tisch School of the Arts, NYU), Jennifer Stob (Yale)

11:45am: Metrum (Ivan Balad'a, Czechoslovakia, 1967, DVD)

Forest (Ivan Balad'a, Czechoslovakia, 1969, DVD)

Silence (Milan Peer, Czechoslovakia, 1969, 35mm)

2:00pm: Birds, Orphans and Fools (Juraj Jakubisko, Czechoslovakia, 1969, 35mm)

The Red and the White (Miklos Jancso, Hungary, 1967, 35mm)

5:00pm Discussion: Katerina Clark, Laura Engelstein, Alice Lovejoy, John MacKay (all from Yale)

7:00pm: The Words of the Chairman (Harun Farocki, West Germany, 1968, 16mm)

La Chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, France, 1967, 35mm)

8:45pm Discussion: Francesco Casetti (Universita Cattolica, Milan), Kristin Ross (NYU), Sally Shafto (Big Muddy Film Festival, Southern Illinois University)

9:30pm: China is Near (Marco Bellocchio, Italy, 1967, 35mm)

Saturday, February 17

9:00am: The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet, West Germany, 1968, 35mm)

Alaska (Dore O, West Germany, 1968, 16mm)

Jum-Jum (Werner Nekes, West Germany, 1968, 16mm)

Raw Film (W. and B. Hein, West Germany, 16mm)

12:00pm Discussion: Thomas Elsaesser (University of Amsterdam), Terri Francis (Yale), Gundula Kreuzer (Yale)

2:00pm: Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed (Alexander Kluge, West Germany, 1968, 16mm)

4:00pm: Notes for a Film about India (Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italy, 1968, DVD)

Black Panthers (Agnes Varda, USA, 1968, 16mm)

5:30pm Discussion: Hazel Carby (Yale), Kathleen Cleaver (Yale), Anita Trivelli (l'Università "Gabriele d'Annunzio", Chieti-Pescara)

7:30pm: Le Revelateur (Philippe Garrel, France, 1967, DVD)

La revolution n'est qu'un debut: continuons le combat (Pierre Clementi, France, 1968, DVD)

9:30pm: The Structure of Crystal (Krzysztof Zanussi, Poland, 1969, 35mm)

For those of my readers who might be in the New Haven area this weekend, Yale will be hosting a film festival and conference focusing on of the most politically-contentious years in the postwar era: 1968. As a point of reference, it is important to note that this is the third such conference hosted at the university, with the first two focusing upon the years 1945 and 1956 respectively. In other words, 1968, with all its connotations, is not the sole purpose behind the conference. This is first the opportunity to screen a number of European films that emerged from the same zeitgeist. While I myself would have preferred a less shall we say "obvious" year -- and one richer in film art -- such as say 1962 or especially 1967 (which you will notice is the year of many of the films screened for the conference anyway), the opportunity to see so many rare works is indeed tantalizing, and not to be missed if you're anywhere close to New Haven. So too will be the discussions that include a number of my former and current professors and colleagues including NYU emeritus faculty Annette Michelson. For those outside the area, I will do my best to blog as much of the event as is possible -- one could say correspondences from the front.

A Film Festival and Conference at Yale University

Thursday, February 15 to Saturday, February 17, 2007

Whitney Humanities Center, 53 Wall St., New Haven, CT

Sixty-Eight! Europe, Cinema, Revolution? will focus on the New Wave cinemas of Eastern and Western Europe leading up to and in the aftermath of the political showdowns of 1968. The European Studies Council, along with the Film Studies Program and the Department of the History of Art, has organized the festival around a wide variety of films from many countries, from little-known gems and avant-garde shorts to recognized cinematic classics. The festival will interlace feature films, documentaries, and experimental films with introductions by scholars and critics from a range of disciplines, and informal panels and open discussions. A complete list of participants and details may be found at http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/europeanstudies/1968

Thursday, February 15

7:00pm Far From Vietnam (Jean-Luc Godard, Joris Ivens, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, France, 1967, 16mm)

9:30pm I Am Curious - Yellow (Vilgot Sjoman, Sweden, 1967, 35mm)

Friday, February 16

9:00am Cinegiornali liberi (Cesare Zavattini et al., Italy, 1968, 16mm)

Classe de lutte (Les Groupes Medvedkine de Besancon, France, 1968, 16mm)

La reprise du travail aux usines Wonder (Etats generaux du cinema, France, 1968, DVD)

10:45am Discussion: Giorgio De Vincenti (Universita di Roma-III), Michael Denning (Yale), Annette Michelson (Tisch School of the Arts, NYU), Jennifer Stob (Yale)

11:45am: Metrum (Ivan Balad'a, Czechoslovakia, 1967, DVD)

Forest (Ivan Balad'a, Czechoslovakia, 1969, DVD)

Silence (Milan Peer, Czechoslovakia, 1969, 35mm)

2:00pm: Birds, Orphans and Fools (Juraj Jakubisko, Czechoslovakia, 1969, 35mm)

The Red and the White (Miklos Jancso, Hungary, 1967, 35mm)

5:00pm Discussion: Katerina Clark, Laura Engelstein, Alice Lovejoy, John MacKay (all from Yale)

7:00pm: The Words of the Chairman (Harun Farocki, West Germany, 1968, 16mm)