The fact that

Russian Ark is comprised of a single, 90-plus minute take might give one the wrong impression: that the picture is primarily a technical tour-de-force. Of course, the details of its production only add to this misconception. To begin with,

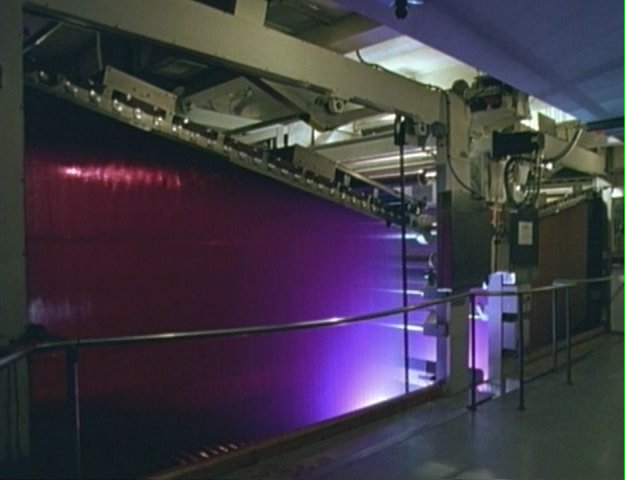

Russian Ark was filmed entirely within the Hermitage of St. Petersburg, which because of its international cultural status required that director Aleksandr Sokurov and his crew complete the shoot in a single day (on the 23rd of December, 2001). After four years of development, filming commenced with over 1,000 actors, three orchestras and countless technicians. Sokurov entrusted the operation of a lone high-definition video camera to steadycam operator Tilman Büttner (

Run Lola Run, 1998), whose task was to realize the director’s vision of three hundred years of Russian history in a single mobile take. Following three false starts, each of which were aborted around the ten minute mark,

Russian Ark wrapped after a successful fourth attempt, thereby making history as the world’s first one-take feature, and achieving the director’s purpose of making a film “in one breath.”

Aleksandr Sokurov was born during the summer of 1951 in the former Soviet village of Podorvikha (located within the Irkutsk district).

[i] As a young adult, Sokurov enrolled in Gorky University where he later earned a degree in history. In 1975, Sokurov switched courses, entering the Producer's Department at the All-Union Cinematography Institute (VGIK, Moscow). There, he soon came into conflict with the school’s administration, forcing the future director to finish a year early after his student works in cinematography were condemned for their formalism and their “anti-Soviet views.” (In hindsight, both accusations were undoubtedly accurate.) Nevertheless, the director’s first feature,

The Lonely Voice of Man (1978-87), which was not accepted for graduation, received numerous prizes and the support of legendary Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, who helped Sokurov find work at the Lenfilm studio in 1980. To be sure, Tarkovsky has remained Sokurov’s primary influence ever since, providing the latter with a template for poetic and one might say spiritual filmmaking. These qualities are apparent in a series of masterworks that include

Days of Eclipse (1988),

The Second Circle (1990) and Sokurov’s signature

Mother and Son (1997), all of which have won numerous international prizes for the Russian auteur.

In fact, Tarkovsky’s impact extends even to

Russian Ark, where Sokurov’s aesthetic echoes the older director’s increasing use of longer takes late in his career (many of which run to six minutes or longer, including

The Sacrifice’s [1986] extraordinary penultimate sequence-shot). However, it is outside of a Russian context that one sees the clearest precursors for Sokurov’s one-take strategy. Both Miklós Jancsó’s

The Red and the White (1967, Hungary) and Theo Angelopoulos’

The Traveling Players (1975, Greece), for example, mobilize long takes and crowd movements to effect temporal passage within the boundaries of a single shot. Similarly in Japan, Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 masterpiece

Ugetsu inaugurated the technique of introducing subjective variation within the space and time of a camera movement, via the director’s presentation of an encounter between the film’s male protagonist and his late wife. Nevertheless, while each of these antecedents attained an unprecedented level complexity in terms of their staging, the limits imposed by Sokurov’s subject created a number of unique impediments, any of which could have ended the production of

Russian Ark permanently: a light burning out at an inopportune time, an actor flubbing his or her lines, or the camera lens steaming up as action moved from the courtyard back into the museum. Anticipating the last of these, Sokurov conducted experiments in a freezer and lacking the conclusive evidence he needed, lit a candle in a church, where he prayed for the success of his shoot.

[ii]

Viewing

Russian Ark in light of the challenges posed by the production, a certain tension – or even drama – is created by the film’s unspooling. Then again, to scrutinize

Russian Ark in these terms would be to miss the point of Sokurov’s adoption of a one-take format (and to deviate from the way in which most spectators attend to the film). Indeed, one of the more remarkable qualities of

Russian Ark is the ease with which the viewer forgets that they are watching a single-take picture. By the time the film concludes, it is less the technical bravura that is in evidence, than the melancholic mood that permeates the nobility’s final exit from the Winter Palace. An overwhelming emotional heft accompanies the film’s denouement, confirming

Russian Ark’s elegiac status, which in its case pertains to the passing of high Russian and European civilization. As the ever-present off-screen narrator (voiced by Sokurov himself) says to his on-screen companion, Sergei Dreiden as the historical Marquis de Custine, “Farewell, Europe.” Thus,

Russian Ark eulogizes not only the pre-Revolution Russian history that is instantiated by Sokurov’s cast of thousands which fill the grand hallways and ballrooms of the Hermitage, but also the beauty and majesty of this waning civilization: it is for the Canova at which the Stranger shouts “Mama” and for Rembrandt’s late masterwork "The Prodigal Son" upon which Sokurov and Büttner’s camera lingers and for Catherine the Great’s priceless china that is used during the dinner service; and it is for the costuming produced by the crew’s sixty-five designers, the music performed by

Russian Ark’s three orchestras, and for the ephemeral qualities of the ball sequence depicted at the picture’s end – that is, for the dances, the gesturing, etc.

Therefore, it becomes clear that

Russian Ark’s title is descriptive of its purpose: namely, to preserve a culture that continues to disappear. Sokurov’s use of the term ‘ark’ to describe this process is far from accidental: as the shot’s digitally-enhanced conclusion makes clear, the museum itself (or perhaps more accurately, the film) is this ark and is “destined to sail forever.” (Sokurov even adds rolling waves to the landlocked wintry exterior.) In this way,

Russian Ark demonstrates both its currency among contemporary European cinema and also its integral position to the director’s oeuvre. With respect to the former,

Russian Ark’s focus on a crumbling civilization situates the film in a fin-de-siècle tradition that also includes Michael Haneke’s

The Seventh Continent (1989), Manoel de Oliveira’s

Abraham’s Valley (1993), Raoul Ruiz’s

Time Regained (1999; Ruiz likewise utilizes the technique of combining tracking shots with zooms to reshape spatial dimensions in his own narrative of time travel). As far as the director’s own corpus is concerned, contrary to the opinion of many critics,

Russian Ark is very much of a piece with many of the director’s previous works:

Russian Ark seems to complete a cycle of films – most of which feature the word ‘elegy’ in their titles – that similarly eulogize. Indeed, as with the director’s previous

Elegy of a Voyage (2001),

Russian Ark tours a museum’s galleries, though unlike that former film or indeed any of the other works that likewise comprise said cycle,

Russian Ark greatly exceeds Sokurov’s previous efforts in terms of the scope of its production. As such,

Russian Ark might just be the endpoint of the director’s aesthetic, and perhaps even its culmination.

[iii]

At the same time,

Russian Ark’s form remains a function of its content, not simply the latest manifestation of a personal style. Again,

Russian Ark depicts three hundred years of the nation’s history – that is, of the transformation in the Hermitage’s use – beginning with Peter the Great (the city’s founder) and ending in the present among the gallery goers, though the narrative follows no similar trajectory. Throughout, the Marquis and the off-camera narrator snake through various historical moments, at times interacting with the palace’s population, and in other instances remaining invisible to the instruments of history. Through their tour a unitary fractal of time and space – a single shot – is maintained, even as the mise-en-scène cedes from one historical moment to the next. In fact, it is Sokurov’s careful delineation of on- and off-camera space that allows so many disparate times to coexist within the museum walls. Not only are new moments in the museum’s history broached when our guides cross through the palace’s thresholds from one room to the next, but indeed the space outside the frame is constantly remaking itself according to its next historical stage, just as Sokurov transforms the disclosed museum that exists before our eyes. Sokurov and Büttner transform on-camera space by pairing their forward tracking camera with zooms that effectively flatten or stretch the space in view, thereby producing a visual analogy for the historical transformations that shape the narrative. At the same time, Sokurov’s insistent use of a single take reaffirms the spatial unity of the museum. That is, if the contents of the space are being transformed over the course of Sokurov’s narrative, its basic scaffolding remains secure. Sokurov’s ‘ark’ therefore is a vessel of time – or multiple times – preserving again far more than the material objects on view in the Hermitage.

Russian Ark enshrines the past, utilizing the specificity of an unbroken sequence of moving images to unite the broad scope of the palace’s history. Thus,

Russian Ark creates a new form of montage that depends not on the juxtaposition of discrete spatial-temporal fragments in sequence, but on the moment-to-moment transformation of the mise-en-scène and on the arrangement of multiple time values in a single space. We may say, consequently, that the shot no longer denotes a united space and time but the potential for multiple times – the history of a space.

Directed by Aleksandr Sokurov

Director of Photography, Steadycam Operator Tilman Büttner

Produced by Andrey Deryabin, Jens Meurer, Karsten Stöter

Screenplay by Anatoly Nikiforov, Aleksandr Sokurov Design

Visual Concept and Principal Image Aleksandr Sokurov

Music Performed by Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra

Conducted by Valery Gergiev

Original Score Sergey Yevtushnko

Presentation of Hermitage Bridge Studio, Egoli Tossell Film AG

Cast Sergei Dreiden….

The Stranger - The Marquis de Custine, Maria Kuznetsova….

Catherine the Great, Leonid Mozgovoy….

The Spy, Mikhail Piotrovsky….

Himself (The Hermitage Director), David Giorgobiani….

Orbeli, Aleksandr Chaban….

Boris Piotrovsky, Tamara Kurenkova….

Herself (The Blind Woman)…. Maksim Sergeyev….

Peter the Great, Vladimir Baranov….

Nicholas II, Anna Aleksakhina….

Alexandra Fyodorovna, Wife of Nicholas II, Aleksandr Razbash….

Military Official

Notes:

[i] The biographical details included in this paragraph were taken from Aleksandr Sokurov’s official site,

Island of Sokurov, which is overall an extraordinary resource on the director’s life and his body of work.

[ii] This last anecdote is included in Knut Elstermann’s fine documentary on the film’s making,

In One Breath: Alexander Sokurov's Russian Ark (2003), which Wellspring featured on its DVD release of the film from that same year.

[iii] In terms of the critical response to

Russian Ark, few if any of the director’s films have been as widely praised in the U.S.: it is, for instance, the only of the director’s films to have been reviewed by Roger Ebert, who gave the picture four stars (out of four) for his Chicago Sun-Times column. Likewise, art house-minded critics Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader) and J. Hoberman (The Village Voice) both named the film as one of the year’s “ten best” in 2002. In addition,

Russian Art is also the director’s only box office success, grossing a respectable $2,326,979 during its U.S. theatrical run, including an impressive $29,022 opening tally on two screens in December of 2002 (courtesy of

Box Office Mojo). To date, Russian Ark has earned more than $6.5 million worldwide, of which forty-five percent has been earned in the United States, making it the seventy-ninth highest grossing foreign language film in this country’s history. These numbers are all the more impressive when one considers that

Father and Son (2004), Sokurov’s most recent film to earn an American theatrical release – also courtesy of Wellspring – has yet to earn $40,000. On the contrary, the director’s highly-acclaimed biography of Japanese Emperor Hirohito,

The Sun (2005) – Cahiers du Cinema’s number one film of the year – remains undistributed. Surely,

The Sun’s inability to secure U.S. distribution emphasizes the void left by Wellspring’s disappearance from the American theatrical landscape.

-screenshot.jpg)